Colonial Americans were well versed in what we would today call sustainability. As noted in R is for Regional Planning, sustainable development was at the heart of James Oglethorpe’s 1733 plan for Savannah. At Savannah, gardens and farms encircled the city’s core, permitting the community to provide for the full range of its needs to maintain both its existence and unique character. Thomas Jefferson also advocated a nation grounded in agriculture and local self-sufficiency. As he put it in 1785 in his Notes on the State of Virginia, “Dependance begets subservience and venality, suffocates the germ of virtue, and prepares fit tools for the designs of ambition.”

Colonial Americans were well versed in what we would today call sustainability. As noted in R is for Regional Planning, sustainable development was at the heart of James Oglethorpe’s 1733 plan for Savannah. At Savannah, gardens and farms encircled the city’s core, permitting the community to provide for the full range of its needs to maintain both its existence and unique character. Thomas Jefferson also advocated a nation grounded in agriculture and local self-sufficiency. As he put it in 1785 in his Notes on the State of Virginia, “Dependance begets subservience and venality, suffocates the germ of virtue, and prepares fit tools for the designs of ambition.”

The benefits of sustainability would re-echo during the nation’s history. Oftentimes, however, sustainability has been overshadowed by countervailing forces, including large-scale manufacturing and mass production of goods, and a heavy and growing dependence on non-renewable resources.

In the 19th century, the benefits of self-sufficiency and a sustainable way of living were most dramatically underscored by Ralph Waldo Emerson and the “transcendentalists,” including Henry David Thoreau, whose account of his two years at Walden Pond still strongly resonates today.

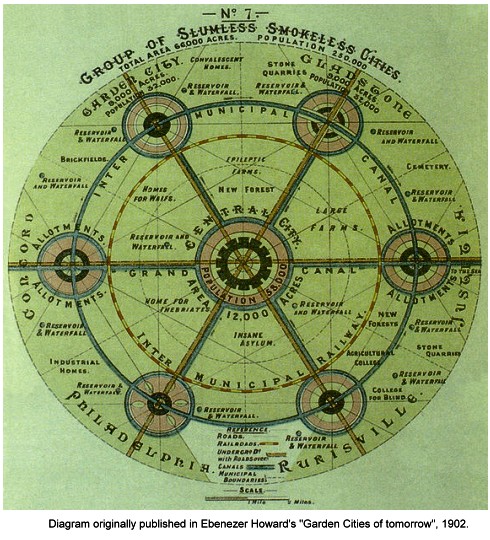

Toward the end of the 19th century, leading planners in England and the United States were seeking ways of balancing explosive urban growth with a sustainable pattern of living. This was especially evident in the Garden City movement pioneered by Ebenezer Howard, which sought to limit the size of cities to about 32,000 people; surround the cities with broad belts of agricultural land; and assure the continued existence of neighborhood-scale commercial, educational, and employment centers. This laid the groundwork for an interest in managing growth, and structuring the community based on stable neighborhood-scale units.

Sustainability on an even broader-scale was championed by the American regional planning movement of the 1920s, led by Benton MacKaye, Lewis Mumford, and others. Regional planners envisioned growth being channeled within metropolitan areas so that small villages and farmland would be preserved against, as MacKaye put it, the “deluge” of metropolitan growth.

While regional planning never truly implemented the vision of its founders (focusing instead on developing highway systems and recreational areas to accommodate growth), the ideal of having city and countryside harmoniously relate to each other and to the natural environment, continued to manifest itself in American planning.

One example was in the continued interest in developing new towns and communities which could meet residents’ needs, not just for housing, but for work, shopping, food, and recreation. This was seen in the greenbelt towns built during the 1930s (Greenhills, Ohio; Greendale, Wisconsin; and Greenbelt, Maryland), and in more recent examples such as The Woodlands, north of Houston. It is also reflected in the growing number of “new urbanist” communities being developed today.

One example was in the continued interest in developing new towns and communities which could meet residents’ needs, not just for housing, but for work, shopping, food, and recreation. This was seen in the greenbelt towns built during the 1930s (Greenhills, Ohio; Greendale, Wisconsin; and Greenbelt, Maryland), and in more recent examples such as The Woodlands, north of Houston. It is also reflected in the growing number of “new urbanist” communities being developed today.

Most sustainable development programs seek to promote compact development, conserve farmlands and woodlands, preserve close-in habitat for wildlife, reduce runoff erosion, promote local shopping areas, encourage energy efficiency, and facilitate walking, bicycling, and efficient transit services. See also E is for Ecology.

Planning for sustainability has also increasingly been linked to concerns about social equity (see J is for Justice). This reflects the view that planners should promote a pattern of development that provides for all segments of American society, not just the uppermost income strata. This includes the opportunity to find an affordable place to live, within reach of job opportunities. The American Planning Association has adopted these goals in its policy guides on housing and on smart growth.