See the previous section of The Local Economy Revolution: Making Room for What Will Be Next.

Today, Della compares the old industrial-era economic development paradigm, which still reigns in many communities, with a newer way of thinking.

“In the end, I don’t want a business here because we gave them the best deal – I want them here because they share our beliefs. If a business is here because they share our beliefs, I bet they will stay here and be more invested in our community than the company that came here just because they got the best deal.”

— William Lutz, “Economic Development: Does your place matter?” (wiseeconomy.com)

Meaningful investment, whether in the person you date, the phone you buy, or the community you choose for your business or your home, is usually based on something deeper than a straight cost-benefit analysis.

Meaningful investment, whether in the person you date, the phone you buy, or the community you choose for your business or your home, is usually based on something deeper than a straight cost-benefit analysis.

Real commitment requires that we find a resonance, some sort of sympathetic vibration between who we are and what we value and what we understand of the other.

In economic development, there’s a tendency to pooh-pooh that kind of talk. It’s a flaky planner thing, like that mushmouthed vision they put in the comprehensive plan that no one reads.

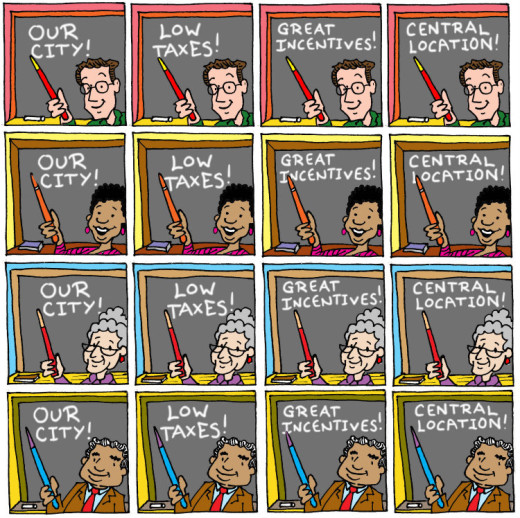

What do businesses want, you ask? Oh, easy.

Low taxes. Big incentives. Access to 75% of the nation’s population within a 600 mile radius. What’s the likelihood that you can really compete on low taxes and access to the same blob of population as every other city within 600 miles?

How does that make you special?

This is an old industrial-era economic development paradigm. It assumes that everyone shopping for a business location just showed up at Wal-Mart: we are looking at a shelf of indistinguishable gadgets, rows upon rows of detergent or paper towels, each with some different buzzword or bright package or stupid bear on the wrapper than has nothing to do with what the thing is supposed to do. We need one, so we grab one — maybe the one we’ve used in the past, maybe the one Uncle Joe works for, maybe the cheapest or the biggest. But most of the time, it’s a purchase without loyalty. It’s functional. It’s the one we pick because it takes the least effort. Whatever.

But what’s the likelihood that we’ll make any effort on behalf of this purchase? Will we make a special trip to a different store if they stop carrying that brand? If they change the formula and it doesn’t work as well with my tap water, will I storm the stockholder’s meeting to insist that they change it back?

Nah, I got other things to do. I’ll just grab something else.

Consumer brands spend literally billions of dollars per year to try to build loyalty to a one-dimensional, interchangeable, disposable thing. We see how well that works.

We who work with communities live in a world of the fascinating, the unique, the irreplaceable. That’s what your mix of people, places, history, culture, economics, etc. gives you. The aspects that make you unique make you valuable.

We who work with communities live in a world of the fascinating, the unique, the irreplaceable. That’s what your mix of people, places, history, culture, economics, etc. gives you.

The aspects that make you unique make you valuable — whether you’re a detergent that really does make whites whiter and brights brighter, or a community with a unique character and a unique place in the world that can provide something of value to a specific type of person or business. Specifically, people who are seeking a place that will give them that resonance.

Why on earth would we settle for being just another of the hundreds of places that have sites, a handful of incentives, a great “work ethic” (whatever that is), and access to some undifferentiated mass of people that are irrelevant to the vast majority of businesses? Blah blah blah. But we often do.

And we try to compensate by cranking on one of those levers on the economic development machine: we throw money at ‘em. After all the only way to stand out from the competition is the way Wal-Mart does: make yourself cheaper, and cheaper, and cheaper than everyone else. Welcome to the Race to the Bottom

Why not claim who we are, what we value, what we want to be …. Put that message out there, start exerting a pull on the people and businesses who might actually want us, not just the cheap inducements we offer?

Then, our places matter. Then there’s a reason for people and businesses to have loyalty, to care what the hell happens here.

Then we have a chance to make a difference.

You’re an old horse and wagon on Mulberry Street, and that’s fine.

The Dr. Seuss book And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street was one of my kids’ favorites when they were younger, and oddly enough, it’s one of his oldest. In the story, a young boy anticipates that when he gets home from school, his dad will want him to describe what he saw on that walk. The boy, of course, has an urge to embroider the story, to make it more interesting, but he knows that will not go over well. So, as he thinks about what to tell his father, he agonizes over the fact that the only thing he saw on the way home was an old draft horse pulling an old wagon.

Not interesting enough. So he starts embellishing … just a little, and then a little more, until what he’s going to describe goes from something the boy thinks is pretty boring to an impossible picture loaded with racing elephants and giraffes, exotic people, Seussian vehicles and an assortment of colorful chaos.

And of course, when the kid gets home ready to tell this wild story, he catches himself and tells the truth.

Here’s the funny part: my kids loved the way the story goes wildly out of control, but they could never figure out why a horse pulling a wagon on a city street wasn’t interesting enough to report by itself. They had a different context: if they saw a horse pulling a wagon on a street on the way home, that would of course be a very big deal. On the other hand, the parade does include an (unnervingly stereotypical) Chinese person using chopsticks. My kids have watched their mother and father “eat with sticks” since they were tiny, so they never understood why that was in the parade.

What was unique and exotic to Dr. Seuss and his character was utterly blasé to my kids, and what was exotic to my kids was a routine part of life for the author when he wrote the book in the 1930s. In this case, that’s a factor of the time difference between the writing and the reading, but what I want you to notice is how differently different people perceived the same environment.

In a previous section I pulled out an old trick of mine: the comparison of a certain location’s native flower to one that’s much more exotic. In that case, it was an apple tree blossom and a hibiscus. The point in that comparison is that the native flower is much easier to grow in that environment. If the point is to produce blossoms as efficiently as possible, with as little special treatment or fussing as possible, the native plant will beat the exotic almost all the time (when it doesn’t, we have a kudzu-weed type problem, but that’s another metaphor for another day).

The horse and wagon on Mulberry Street story puts another twist on the native/exotic issue: what is routine from one perspective is crazy amazing for another. A person eating with chopsticks is not anything I would give a second glance. But a horse and wagon trundling down the street in front of my window would definitely get my attention.

The auxiliary of that point is that your community will not be unique, and therefore more valuable, to everyone. If I am not interested in horses and wagons, or chopsticks or low water rates or warehouse space or mountain climbing, and that is what makes your community unique, I am not going to consider your community more valuable than anywhere else.

But someone else, someone who wants those amenities, will. And since that someone else will regard your community as having more value, as being worth more, there’s no point in wasting the limited resources you have chasing me, when you could be putting your effort into chasing him or her.

That means that we have to do three things well:

1. We need to understand very clearly what makes our community unique. That’s not just something we can pull out of the air, out of our usual assumptions and our portfolio of past ad campaigns. That’s something that we need to analyze, put together data about, make sense of.

We have to make sure that we are seeing the community the way an outsider without our emotional baggage and history will.

Maybe more importantly, we have to make sure that we are seeing the community the way an outsider without our emotional baggage and history will. You can do that, but it requires a very strong emphasis on the outside perspective. And most importantly, it must be true.

2. We need to articulate what makes us unique

— and articulate it not just once, not just through the channels that we are used to using, but as broadly and consistently as possible. Once isn’t enough. Once is an anomaly to the reader or listener — a novelty, not a compelling argument. That doesn’t mean that we have to flog the same story, the same three talking points, over and over. It does mean that our understanding of what makes us unique must include a variety of threads that together create a compelling image. It’s our job to weave those threads together for the reader or listener, and that will take a sustained effort, not just a weeklong Facebook push.

We need to find ways to get our message to the people who are most likely to value what makes us unique.

3. We need to target what we do and what we offer.

The glossy ad in Business Week with the aerial view of your industrial park has long since outlived its usefulness, if it was ever effective to begin with.

Instead, we need to find ways to get our message to the people who are most likely to value what makes us unique.

That might mean ads, but in the evolving environment in which people access and consume information, it’s more likely to mean web-enabled tools that open up communication with people who are likely to care.

That’s a long-winded way to say “social media” (fast climbing my despised terms list). Regardless of how you feel about Twitter or how much you worry about privacy on Facebook, the opportunity that we have today is to talk directly to the people who are already looking for what we have to offer. It’s not difficult and it’s not costly. But it does take time and concerted effort.

Editor’s Note: For more on the importance of identifying what makes your community unique, see ULI senior analyst Ed McMahon’s remarks in: “What’s the Market Telling Us?” and his series, “The Secrets of Successful Communities,” starting with “Have a Vision for the Future.”

Coming Next from The Local Economy Revolution: The Real Power of Small Businesses