What’s the matter with kids today? In large part it’s that we’re not providing them with a child-friendly built environment. That was the message at the heart of Suzanne Crowhurst Lennard’s talk at the International Making Cities Livable conference in Portland, Oregon.

What’s the matter with kids today? In large part it’s that we’re not providing them with a child-friendly built environment. That was the message at the heart of Suzanne Crowhurst Lennard’s talk at the International Making Cities Livable conference in Portland, Oregon.

Lennard, who holds a PhD in architecture, has written extensively on how the built environment affects our mental, social, and physical health, including Livable Cities Observed and The Forgotten Child (both co-authored with her late husband Henry Lennard — with whom she also co-founded the IMCL conferences in 1985).

As Lennard pointed out in her remarks to conference attendees, in many places today the built environment has, unfortunately, been a key factor in children being less independent and physically fit than they should be.

Editor’s note: In terms of health impacts, take a look back at what Dr. Richard Jackson had to say about the impacts of not having walkable communities. As Jackson pointed out, obesity rates have been rapidly rising — especially among children. Not only will this be bad for these kids as they grow up with much higher rates of diabetes and other health problems, but it will be bad for the country — with all of us absorbing part of the huge medical expenses this will entail.

Lennard spoke about the developmental impacts that the lack of vigorous outdoor activity and exploration can have on children.

Lennard spoke about the developmental impacts that the lack of vigorous outdoor activity and exploration can have on children.

The built environment of too many suburbs — and cities as well — fails to provide children with good, safe places to play, explore, and gain independence, she said. What’s more, parents, out of fears about safety, often keep their children at home or limit their play to more formal playground areas, where there’s less opportunity for kids to gain self-confidence. (More on this later in the post).

“Kids need to develop motor skills,” Lennard commented, “for example, by climbing trees, biking, or skateboarding.”

Lennard pointed out that “Edward O.Wilson wrote that nature is the most information rich environment children will ever encounter.” While agreeing, she added: “but the city can also provide interesting, strange, and wonderful things for kids to learn from.”

Lennard mentioned several ways in which cities can provide this kind of enriching environment:

— Cities can help children to learn abstract thought, categories, and relationships “by allowing them to experience different types of buildings and streets, and different patterns in street layout.”

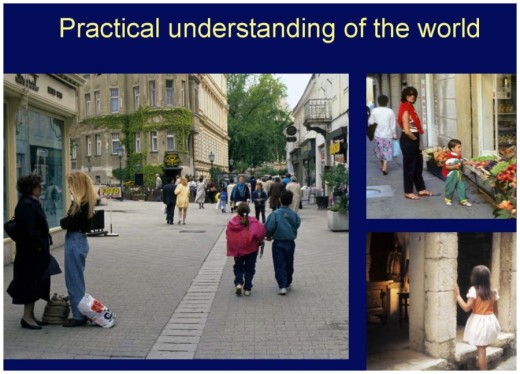

— Cities can provide children with a “practical understanding of the world, especially when they can see what’s going on inside of buildings.”

— Cities can give children a social context where they can see how adults relate to each other, and emulate adult behavior.

— Cities can even provide kids with “an appreciation of beauty, something that is absolutely essential,” Lennard said, adding that “many children admire and enjoy architecture.”

The bottom line, Lennard noted, is that our “built environment must improve our quality of life, not just our standard of living,” and that means “we need child friendly accessibility, and a welcoming built environment.”

Editor’s Note: A Word about Beauty

I found Suzanne Lennard’s comment about the importance of beauty quite interesting. In The Forgotten Child, she and Henry Lennard expand on this. Here’s an excerpt:

“Beauty is important to every child, perhaps especially to disadvantaged children. And yet, in the twentieth century, we have permitted cities to evolve with vast areas that are so ugly that, if we can, we adults flee the city as fast as our cars can take us, leaving the poor, and the children of the poor to bear them as best they may. …

In a beautiful city appreciation of the underlying principles — harmony, proportion, appropriate relationships, continuity and unity — may be perceived by the child as a prescription for behavior.

So also, in an ‘ugly’ city one may discern underlying principles that govern the built environment, such as uniformity and featurelessness, conflictual relations among buildings, uncontrolled development, and these also may serve as presecriptions for children’s behavior.”

The Quality of Play

While several other speakers at the IMCL conference also spoke to several of the points Lennard made, I want to summarize a presentation by Professor Lamine Mahdjoubi, who outlined an interesting research study he was involved with.

Mahdjoubi, who teaches at the University of the West England in Bristol, discussed a study he conducted in a Bristol suburb. It focused on 63 children, age 6 to 10, and examined the “quality of their play” — its frequency, duration, intensity, and the extent of social interaction the kids had.

Each child was fitted with an accelerometer and a GPS device, so the researchers could track where kids played each day and how actively they played.

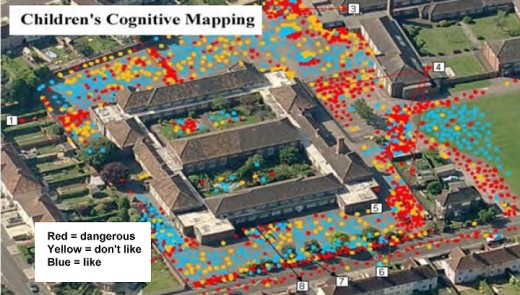

Using 3D maps, the children were also asked to put dots on spaces they liked; spaces they didn’t like; and spaces they thought were dangerous.

One immediate result: the local school relocated its parking areas. In the kids’ mapping, many had highlighted the car parking area as a dangerous place — as it was located in an area where many kids had to cross through.

Among the findings Mahdjoubi highlighted:

- Children who played more frequently and longer, spent more time playing in informal spaces in the neighborhood than the playground.

- In contrast, children who spent less time playing, tended to use the playground more — but spent fairly short periods of time there. For Mahdjoubi, one explanation for the shorter time spent in playgrounds is that parents usually accompany the kids there, and after 20 minutes or so the parents start to get fidgety and want to head home.

- Kids using playgrounds also made fewer new friends than those spending more time in informal play areas.

The study, Mahdjoubi explained, shows the importance of having neighborhoods where kids can expand their range of play areas. “We need to provide a network of play areas, with more diverse natural and physical surroundings that offer a greater the range of learning and developmental.” “We also,” he added, “need to reclaim streets from the cars, and bring them back to children,” noting that “streets used to be the main place children played.”

Mahdjoubi made one final point — one that echoed a comment Suzanne Lennard had made earlier — “it’s very important for us to shift the debate from risk to challenge.” While Mahdjoubi didn’t discount the importance of having a safe environment (in fact, he stressed it), he reminded us that “a certain level of injury and exposure to some risk is essential to children’s development.”

OK, you’ve finished reading the post. Now relax for five minutes and enjoy this video about a creative British organization (also based in Bristol) called Playing Out. It shows how a neighborhood street can become a child-friendly wonderland. Thanks to International Making Cities Livable for alerting us to this video via their Facebook page.

Update: August 11, 2013 – After posting this article, we received a reminder from a reader about Cat Stevens’ old song, “Where Do the Children Play?” Here’s one of several versions available on YouTube.