Dr. Richard Jackson, MD, MPH, has the look of a thoughtful professor — or of a caring physician — and he’s both. But he also brought a passion and a clarion call to action to the opening session of the International Making Cities Livable conference in Portland, Oregon.

Over the past decade, Dick Jackson — who is Chair of Environmental Health Sciences at UCLA’s School of Public Health — has been one of the leading voices in the health care community speaking to the connection between a variety of diseases and how we build, and live in, our communities. As he succinctly put it, “the built environment is health policy and social policy in concrete.”

There’s strong precedent for linking planning and public health, Jackson reminded the audience. At the start of the 20th century, the leading causes of death were pneumonia and tuberculosis. Health advocates and planners came together to advocate for more open space, parks, and more light and air between buildings. We still benefit from that legacy.

While the primary diseases we face have changed, they’re also connected with how our communities are built.

And what’s the number one cause of death for people between the age of 3 and 34 … it’s traffic crashes.

In 2009, 33,808 people died in car crashes across the country.

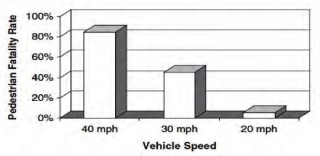

As Jackson noted, how we plan our streets can make a big difference. Being able to drive faster comes with a price tag, as higher speeds lead to sharply increased pedestrian fatality rates.

Jackson — who is also former Director of the CDC’s National Center for Environmental Health — gave his presentation with the precision of a research professor and the visual documentation of a GIS specialist. Map after map made the case for the impact our built environment has on health. As Jackson noted, with the hint of a smile, “every elected official understands maps.”

Take a look, for example, at a couple of his slides showing obesity trends.

“As obesity rates go up, so does the risk of diabetes,” he added.

“And don’t forget that 2 percent of America’s gross domestic product goes to dealing with diabetes.”

Percentage of U.S. adults with diagnosed diabetes: 1994; 2001; 2007.

How do you prevent obesity: through increased physical activity.

Americans realize they’re not as healthy as they used to be, continued Jackson, citing a recent study that found that 20 years ago 32 percent of Americans between 46 and 64 years of age reported themselves as in “excellent” health — compared to just 13 percent today.”[ref]”The Status of Baby Boomers’ Health in the United States: The Healthiest Generation? JAMA Internal Medicine, Feb. 4, 2013.[/ref]

Not surprising given that the percentage of people who acknowledge engaging in no regular physical activity has shot up from 17 percent to 52 percent.

One of the key solutions, said Jackson, is straightforward: “We need to be doing a lot more walking.” But that means we need to build or retrofit our communities so that people can more easily walk in them.

Kids can’t get to most schools by walking or biking. In 1969, 48 percent of school age children walked or biked to school; by 2001 that had plummeted to less than 16 percent. [ref]”Children’s Active Commuting to School: Current Knowledge and Future Directions,” Preventing Chronic Disease: Public Health Research, Practice, and Policy, July 2008, CDC.[/ref]

People are realizing what they’ve lost, Jackson argued, pointing out that “the marketplace is changing; more than 56 percent of homebuyers say they want walkable places.”

While walking is key, Jackson also painted a much broader picture of the challenges facing our nation. He noted that “stuff that’s good for us to eat is twice as expensive as in 1980; food that is bad for us is half as expensive … there’s an enormous increase in high fructose corn syrup in what we eat.” As a matter of policy, “we absolutely need to be taxing sugar; we tax alcohol and tobacco; and fructose is virtually as lethal. A national tax of 1 cent per ounce of sugar sweetened beverages would decrease consumption by 23 percent and raise 14.9 billion.”

From “Agriculture Policy Is Health Policy,” by Dr. Richard Jackson, et al (Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition, Dec. 2009):

“Americans are eating more food, most of which is unhealthy. Between 1970 and 2000 the average consumption per person of added fats increased 38% and average consumption of added sugars increased 20%. … The price of fresh fruits and vegetables increased 118% from 1985 to 2000, and the price of fats and oils increased only 35%. Consumers are price sensitive, such that even small changes in the price of healthy foods affect their consumption. …

Agricultural policy subsidies come at a cost to public health. The system provides all consumers with excess fats and sugars, but especially vulnerable are children and the poor. Lifetime dietary patterns—healthful or not—are generally set early in life. Unhealthful patterns are important; obese children are likely to remain obese into adulthood. … Freedom of choice for consumers is desirable, yet we have a food system that increasingly limits healthy choices for large segments of the population, making unhealthy eating the default option.”

Jackson also stressed the importance of planners and public health professionals working more closely together. Indeed, his audience at the IMCL conference represented a mix of both professions in attendance.

After his talk, I sat down with Dick Jackson, to ask him about strategies for better connecting public health professionals and planners. But first Jackson told me, “be sure to remind your readers that the health community possesses powerful data that supports planners arguments.”

So how do you make connections between two very different professions? “Sometimes,” Jackson said, “planners and public health advocates need a convening group. It needs to be someone’s job to create a joining of the two.”

“The key thing,” he went on, “is to develop personal networks and hold events where both planners and health professionals can connect.” One benefit, he noted, is that you’ll then “know doctors or other public health professionals who you can ask to show up at specific public meetings where their input will make a difference, whether it involves things like the need for a walk to school program or support for proper sidewalks.”

Jackson told me of the value of “cross-training of young planners and young public health professionals,” something he helps to do through his classes at UCLA.

As our interview was drawing to a close, Dick Jackson sounded very much like noted environmentalist Bill McKibben, as he stressed: “We need to be leading more mindful lives. We’ve got to address climate change, and we have to realize that the era of waste is over.”

Getting up to walk back upstairs to the conference, Jackson looked straight at me and said: “You know what gives me the most hope … it’s the young people; they understand.“