“Polls consistently show that people are concerned about the quality of their drinking water [and the value of protecting drinking water sources] … For 66% of those people, their water comes from a river, lake, stream, or other surface water source. The remaining public water system consumers are drinking water from groundwater source … All the bodies of water we work to clean up and protect are somehow connected to somebody’s drinking water.

This can be a powerful mobilizing factor [for restoring and protecting our source waters].” 1

– Lynn Thorp, National Campaigns Director, Clean Water Action

– Gayle Killam, Deputy Director of River Network’s Rivers and Habitat Program

Two main federal laws keep our water clean — the Clean Water Act (1972) and the Safe Drinking Water Act (1974). The Clean Water Act regulates what we put into our water bodies; the Safe Drinking Water Act regulates public water systems which treat and provide the drinking water to 66% of us. In the 40 some years since they were signed into law, the Clean Water Act and the Safe Drinking Water Acts have worked in tandem to achieve the goals of “fishable, swimmable and drinkable water.” 2

But the nation’s water bodies still face major challenges. According to the EPA’s National Water Quality Inventory, many of our water sources are “impaired” — 44% of one-half million miles of assessed rivers and streams; 64% of 16 million acres of assessed lakes, reservoirs and ponds; and 30% of 25,000 plus square miles of assessed estuaries. 3

The EPA has further estimated that “the nation’s drinking water utilities need $384.2 billion in infrastructure investments over the next 20 years for thousands of miles of pipe as well as thousands of treatment plants, storage tanks, and other key assets to ensure the public health, security, and economic well-being of our cities, towns, and communities. 4

Yet, the nation’s lawmakers seem less committed to clean water than the American public. Since January 2011, the House of Representatives has voted numerous times to roll-back key provisions of the Clean Water Act. This trend is mirrored in North Carolina where lawmakers are challenging existing water quality laws. In particular, the delay — yet again — of the Jordan Lake Rules.

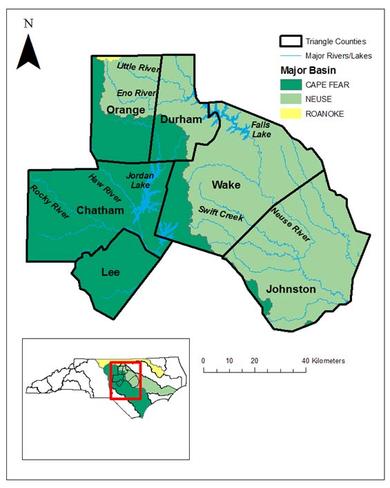

Triangle Source Waters

The Triangle’s growing population and development rate are putting a high demand for publicly supplied water and thereby increasing the level of impairment in the region’s rivers, lakes, and river basins.

The Triangle’s growing population and development rate are putting a high demand for publicly supplied water and thereby increasing the level of impairment in the region’s rivers, lakes, and river basins.

The sources of pollution are two fold. Point source pollution from factory discharges and sewage treatment plants and non-point source contamination from fertilizers, pesticides, and sedimentation that enter streams, rivers, and groundwater.

Jordan Lake Rules

The B. Everett Reservoir — Jordan Lake — is part of the Cape Fear Basin in the Triangle. The 13,940 acre lake was formed with the construction of a dam on the Haw River in 1982 to provide flood control, water supply, downstream water quality protection, fish and wildlife conservation, and recreation.

Jordan Lake is a source of drinking water for 300,000 residents and a recreational area for more than a million residents.

Water quality impairment from pollution caused by fertilizers, sediment, and toxins flowing downstream from the lake’s streams and tributaries has always plagued Jordan Lake. The Clean Water Act requires that states reduce nutrient pollutants that cause water quality violations by adopting a “Total Maximum Daily Load” (TMDL) for the pollutants causing the problem. In September 2007, the EPA approved North Carolina’s Jordan Lake Nutrient Management Strategy and the Jordan Lake Rules were signed into law in 2009.

The Jordan Lake Rules mandate reducing pollution from wastewater discharges, stormwater runoff, agriculture, and fertilizer application in both new and existing development in the Jordan Lake watershed’s 38 municipalities in the Triangle and Triad regions.

Although most local governments in the Jordan Lake watershed took action to meet the Rules’ nutrient reduction targets, requests from some local governments have led legislation every year since 2009 to extend the time allowed for upgrading wastewater treatment and revising local stormwater programs. 5

The Jordan Lake Water Quality Act

But the rules were never fully implemented and in August 2013, the North Carolina General Assembly passed Senate Bill 515, Jordan Lake Water Quality Act, into law.

The bill will continue the current Jordan Lake water quality measures, including Protection of Existing Riparian Buffers Rule, but delay additional measures for three years. 6 The bill modifies the “Protection of Existing Riparian Buffers” rule to allow some exempt uses.

The bill also includes the provision to use $2 million from the Clean Water Management Trust Fund for a study of buoy circulator technology as a way to purify the lake water.

Stakeholders Respond

The response to SB 515 from environmental groups and lawmakers has been strong and varied. Some deemed the water treatment solution unfeasible saying it could never work in a reservoir the size of Jordan Lake — or that it should be tested in conjunction with the Jordan Lake Rules, giving the rules a fair chance to reduce pollution before it enters the water bodies.

Others backed the amended bill and the opportunity to study technologies that may clean the lake in a more cost effective and efficient way than installation of runoff-filtering devices as per the Jordan Lake Rules.

How are local governments going to respond to SB 515? According to Jason Robinson of North Carolina’s Department of Environment and Natural Resources, about one-third of the 38 local governments began voluntarily implementing their Jordan New Development Programs in 2012. Most likely, the local governments that have not yet begun implementing voluntarily will continue to wait until August 2017 — the new deadline.

However, Stan Meiburg, the EPA’s Acting Administrator for Region 4, has indicated that the delay of the Jordan Lake rules does not relieve the state of its obligation to achieve the pollution reductions called for in the 2007 EPA approved TMDL. He has also indicated that federal law does not allow use of treatment technology as a substitute for actually reducing the pollutants being discharged to Jordan Lake. 7

Creative Solutions

Reducing nutrient pollution can be a real environmental policy challenge because of the number of different pollution sources and the onus on upstream communities to spend money for water quality improvements that do not directly benefit their citizens.

While Jordan Lake provides drinking water and recreation in the Triangle, much of the pollution flows from the upstream communities in the Triad region. Although these communities have upgraded their treatment plants, rules that would limit housing development (wider steam buffers, stormwater ponds) are perceived as a hindrance to economic development. Thus the delays.

One way to ease the burden of nutrient reduction on upstream communities is to create a cost-sharing plan so downstream communities that benefit from upstream pollution controls can help offset the cost. Exploring innovative financing of pollution controls, rather than delaying the Jordan Lake rules, would have been consistent with the Clean Water Act and less likely to provoke an EPA response with eventually more burdensome federal pollution reduction standards for local governments.

In some parts of the country, engineering measures to solve water quality problems have been supplanted by “good environment to produce good water” approaches.

The New York Catskill’s public land conservation, watershed protection, and environmentally-friendly farm program have led to: an 80% reduction in agriculture related pollution of the Delaware River Basin; pristine drinking water quality in New York City; and savings of billions on advanced treatment of drinking water. 8

Closer to home, the Triangle’s “Upper Neuse Clean Water Initiative” 9 partnership conserves the most important tracts of land in order to protect water quality. Forests, wetlands, and open fields allow rain and run-off to filter gradually through the soil reaching streams, rivers, and reservoirs. As of April, 2012, 63 properties that include 63 miles of stream banks on 6,170 acres have been conserved, with another 12 properties having 24 miles of stream banks on 2,210 acres in the works.

These watershed communities have demonstrated that clean water is an absolute value with precedence over all other community development goals.

After all, to quote an oft heard phrase from Mayor Randy Voller of Pittsboro, North Carolina, “No Water, No Town.”

Chatham Park on Jordan Lake

Preston Development has requested the Town of Pittsboro establish a Planned Development District (PDD) by rezoning for 7,120 acres In the Southwest Shore Wilderness, one of the largest remaining unfragmented areas in the six-county Triangle region.

Understanding that ecology is integral to planning and development and that the natural environment is the underpinning of all life and habitats, residents are voicing their concerns. The concerns run the gamut from impacts on water quality and supply, wildlife habitats, social justice, community character, and public input to the planning process.

Residents are requesting a slow down on decision-making on the PDD rezoning and a comprehensive study of the impacts on the socioeconomic and natural environment of both the site and greater Pittsboro.

Residents remain hopeful that the developer’s master plan will result in a first class, 21st century, conservation-oriented development incorporating many of the recommendations made by the Triangle Land Conservancy and the results of the requested comprehensive study.

In my next post, I’ll review the Chatham Park PDD and community input process, and discuss some of the broader implications of the approach being taken.

Deepa Sanyal is a Community Planning consultant and Training Professional. She provides professional services to local governments, communities, universities, and civic organizations seeking guidance on comprehensive planning, community assessments & revitalization, historic preservation, and cultural tourism. Deepa also advocates for and writes about sustainable development issues, and serves on the Chatham County Planning Board in her “Corner of the Triangle.”

We welcome discussion of this article on our PlannersWeb LinkedIn group page.

Notes:

- Lynn Thorp & Gayle Killam, “Lets start at the very beginning,” River Voices, Volume 6, Number 3, 2006 (River Network). ↩

- See Lynn Thorp, “Drinking Water and the Clean Water Act” (Clean Water Action web site, Oct. 17, 2012). ↩

- National Water Quality Inventory: Report to Congress, 2004 (U.S. EPA). ↩

- See Drinking Water Infrastructure Needs Survey and Assessment: Fifth Report to Congress, 2013 (U.S. EPA). ↩

- See “Cross-Over Continued: Repeal of Jordan Lake Water Quality Rules” (SmithEnvironment Blog, May 13, 2013). ↩

- See North Carolina League of Municipalities, Staff Analysis of the Legislation ↩

- As reported in “Delaying the Jordan Lake Rules” (SmithEnvironment Blog, July 11, 2013). ↩

- See, e.g., “How New York City Kept Its Drinking Water Pure – In Spite of Hurricane Sandy,” by Albert Appleton and Daniel Moss (Huffington Post, Nov. 5, 2012) and “How New York City Used an Ecosystem Services Strategy Carried out Through an Urban-Rural Partnership to Preserve the Pristine Quality of Its Drinking Water and Save Billions of Dollars,” by Albert Appleton. Note that Applleton has served as a Senior Fellow with the Regional Plan Association and as New York City Commissioner of Environmental Protection and Director of the New York City Water and Sewer System. ↩

- Upper Neuse Clean Water Initiative, on Conservation Trust for North Carolina web site. ↩