On October 29, 2012, the rising Hudson River tides, driven by the approach of Superstorm Sandy, forced me and dozens of my neighbors out of our homes in Yonkers, New York. But we were among the lucky ones as damage to our building was minimal and no one was injured. But countless others in the New York City metropolitan area were not so fortunate.

What’s more, the extensive damage and loss of life caused by Sandy made very real to millions in the New York region the “academic” predictions of the impacts of rising sea levels on coastal communities.

Climate change, whether driven by natural or human sources, is manifested in the impacts of changing weather patterns, including increased drought and fire risk; more intense blizzards; and rising sea levels. I’ll be focusing on the last of these today and tomorrow, in discussing how the New York City region has responded to climate change and the recent impacts of two major storms.

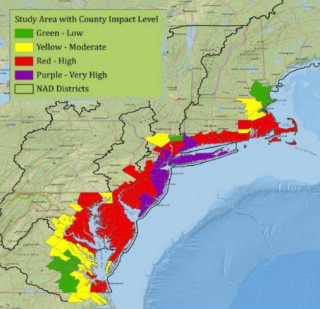

The region, as defined by the Regional Plan Association, encompasses 31 counties in the New York-New Jersey-Connecticut area — home to over 20 million people. With the arrival of Hurricane Sandy on October 29, 2012 (and Irene the year before), the metro area was made very aware of its relationship with the ocean — a relationship that is likely to grow progressively more deadly in the decades ahead.

The scale of the impact of these events have ignited a popular response to the enormity of the task and a wide ranging public discussion of appropriate responses to the region’s relationship with the ocean.

Responses to Climate Change

Responses to climate change can be categorized, in a broad sense, as involving either “mitigation” or “adaptation” strategies.

Mitigation strategies focus on policies aimed at reducing the emission of greenhouse gasses in order to slow or ultimately halt the effects of climate change. These include, for example, the promotion of alternate fuel sources or improvements in energy efficiency.

Adaptation strategies, in contrast, focus on adjustments to the effects of climate change. In the case of coastal settlements, this might include changes to land use policies, infrastructure location, or coastal protective measures.

At the core of both adaptation and mitigation strategies is the idea of resilience — the ability of a community to withstand and respond to the effects of climate change.

At the core of both adaptation and mitigation strategies is the idea of resilience — the ability of a community to withstand and respond to the effects of climate change.

By their very nature, government agencies and non-government organizations (NGO) will concentrate their efforts on mitigation or adaptation strategies that are consistent with their role or mission.

At the state level, broadly we are beginning to see the release and implementation of plans and policies aimed at climate change. In Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York they serve to guide action at the state level and provide a framework for local governments to respond to the impacts of climate change.

- In 2013, Connecticut’s Department of Energy and Environmental released its Climate Preparedness Plan.

- In 2007, New Jersey enacted the Global Warming Response Act, which has targeted statewide limits on greenhouse gas emissions.

- In 2009, New York issued executive Order 24, setting a goal to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in New York State by 80 percent below the levels emitted in 1990 by the year 2050.

These broad policy commitments have, for the most part, focused on a strategy of mitigation in state operations, combined with incentives for the private sector to do the same. In addition, there have been statewide programs that support the development of mitigation and adaptation strategies at the local level.

Sustainable Jersey

In 2009, Sustainable Jersey was created — a non-profit, non-partisan organization underwritten by state grants and private donations — that provides tools, training, education, and financial incentives through a certification program to support and reward communities as they implement sustainability policies.

In 2009, Sustainable Jersey was created — a non-profit, non-partisan organization underwritten by state grants and private donations — that provides tools, training, education, and financial incentives through a certification program to support and reward communities as they implement sustainability policies.

Over 400 of New Jersey’s 565 municipalities are certified or working toward certification. Benefits for communities from participating include recognition certification offers, as well as access to grants and technical support from public utilities, government agencies, and corporations. Certification is a rigorous process requiring municipalities to complete of a range of mandatory and “priority” actions, earning points through the implementation of sustainable programs, land use and transportation policies, and other projects.

A brief video overview of Sustainable Jersey:

Following Superstorm Sandy, Sustainable New Jersey (working with FEMA) developed what it calls the Resiliency Network, a clearinghouse connecting the expertise of professionals and academics with communities in need. 1

Sustainable Jersey may be unique in the country as a statewide non-profit providing comprehensive sustainable support to municipalities.

According to Linda Weber, a planner at Sustainable Jersey, this organization may be unique in the country as a statewide non-profit providing comprehensive sustainable support to municipalities. Weber noted that other states have contacted Sustainable Jersey to learn more about their approach. 2

Status as a non-profit organization provides greater autonomy and flexibility to craft and operate programs, as well as more easily partnering with agencies and the private sector to serve their mission. The implementation of this program has changed the community paradigm regarding sustainability and climate change through its requirement for public participation, moving these issues to the forefront in peoples’ minds.

Climate Smart Communities

Like Sustainable Jersey, Climate Smart Communities (CSC) in New York is a state-local partnership created to meet the economic, social, and environmental challenges that climate change poses for local governments. Unlike Sustainable Jersey, CSC is a state program, operating within New York’s Department of Environmental Conservation.

Like Sustainable Jersey, Climate Smart Communities (CSC) in New York is a state-local partnership created to meet the economic, social, and environmental challenges that climate change poses for local governments. Unlike Sustainable Jersey, CSC is a state program, operating within New York’s Department of Environmental Conservation.

Mark Lowery, a climate policy analyst at CSC describes their role as providing guidance on land-use, encouraging smart growth, and assisting communities with the creation of “individual service plans.” 3 Working through private sector professionals, they meet with communities, who assign leaders and task forces to develop and implement programs and provide expertise to assist municipalities in accessing grants and interpreting technical information. A byproduct of this effort is development of best practices, shared in the CSC network by participating communities. One of the challenges they face as a state agency is the strict definition of the role they play and the work they do.

Regional Plan Association

At the regional level, the metropolitan area benefits from the work of the Regional Plan Association (RPA) — America’s oldest independent urban research and advocacy organization. RPA works at a regional level developing plans that, while they have no regulatory authority, provide an impetus to state and local planning efforts. As a nonprofit, RPA also has considerable flexibility and is not bound by jurisdictional or legislative limits. This makes it easier to address issues that impact the entire metropolitan area, such as climate change.

RPA is currently developing its Fourth Regional Plan — a multiyear research and public engagement initiative to create a comprehensive blueprint for the New York-New Jersey-Connecticut metropolitan region’s growth, sustainability, good governance, and economic opportunity for the next 25 years. They are doing research looking at the state of the metropolitan region — with climate change as a major pillar of the new regional plan.

RPA is currently developing its Fourth Regional Plan — a multiyear research and public engagement initiative to create a comprehensive blueprint for the New York-New Jersey-Connecticut metropolitan region’s growth, sustainability, good governance, and economic opportunity for the next 25 years. They are doing research looking at the state of the metropolitan region — with climate change as a major pillar of the new regional plan.

New York City

At the local level, New York City’s Department of City Planning (DCP) has initiated a number of studies and plans related to climate change:

— Neighborhood Vitality: Through its “Resilient Neighborhoods Initiative,” DCP works with communities to identify changes to zoning and land use and other actions that support the vitality of neighborhoods and helps residents and businesses withstand and recover quickly from future storms and other climate events.

— Climate Resilience: DCP, in collaboration with other city agencies, has undertaken a number of studies focused on identifying and implementing land use and zoning changes, as well as other actions needed to support the short-term recovery and long-term vitality of neighborhoods affected by Hurricane Sandy and other areas at risk of coastal flooding.

— Vision 2020, NYC Comprehensive Waterfront Plan: This major ten-year plan sets the stage for expanded use of the city’s waterfront areas for parks, housing, and economic development, and its waterways for transportation, recreation, and natural habitats.

The Waterfront Plan won the American Planning Association’s 2012 award for best comprehensive plan:

Other Work Being Done

The preceding paragraphs have introduced you to just some of what is being done to address climate change in the New York City metro area. Other major sources of technical support that deserve mention are academic institutions and federal agencies. Three examples include the Stevens Institute, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and HUD.:

— The Stevens Institute in Hoboken has developed the New York Harbor Observing and Predicting System (NYHOPS). This detailed model of tidal and storm flows, enables municipal and other agencies to better assess shore protection initiatives, zoning plans, and community vulnerability to rising sea levels and weather events.

— The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ North Atlantic comprehensive study has used computer modeling and GIS analysis to develop risk reduction strategies. This data is also available to municipalities.

— HUD’s Sustainable Communities Regional Planning Grant Program is funding “Sustainable NYCT,” a collaboration of cities, counties, and planning organizations in the New York-Connecticut region. This program supports metropolitan planning efforts among multiple communities addressing climate change. HUD is also undertaking the creative “Rebuild by Design” program, which we’ll look at tomorrow.

Some Additional Observations:

What we are seeing in the NYC metropolitan area is a multi-faceted approach to dealing with climate change.

What we are seeing in the NYC metropolitan area is a multi-faceted approach to dealing with climate change, including guidance and support of communities from federal, state, regional, academic, and non-profit agencies.

In conversations I have had, there is still limited collaboration among communities at the local level. This may be due to a lack of strong regional structures that would promote increased local collaboration, or to the long tradition of home rule in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut, with municipalities having the final say on most all land use related issues. In any case, this is gradually changing given the challenges, complexities, and costs of dealing with climate change.

Tomorrow, we’ll look at an interesting example of how one small city in the New York metro area is taking steps to better prepare itself for sea level rise.

James ‘JR’ Ronczy is a licensed architect with over 30 years of experience in housing, urban design, mixed-use and transit-oriented development across the country.

JR recently completed work on a Master of Planning and MBA from the University of Colorado and brings a multidisciplinary perspective on issues that relate to housing, urban planning, and responsible land development. He currently works and resides in the New York metropolitan area.

List of Resources:

- Connecticut Climate Preparedness Plan

- New Jersey Global Warming Response Act

- Sustainable Jersey

- New Jersey Resiliency Network

- Draft New York State Energy Plan (2014)

- Climate Smart Communities (New York)

- Plan NYC

- Regional Plan Association

- Regional Plan Association, “Fragile success”

- US Army Corps of Engineers Comprehensive Study

- Stevens Institute (NYHOPS)

Notes:

- NJ Resiliency Network web site. ↩

- Phone conversation with Linda Weber (June 3, 2014.) ↩

- Phone conversation with Mark Lowery (June 1, 2014). ↩