Since history, historic resources, and historic preservation are generally not subjects most people think about very much, these next few posts will provide an introduction and help stimulate your thinking and curiosity.

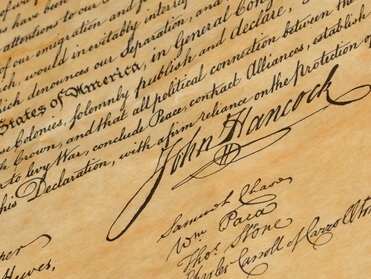

I’d like to start by asking you to give some thought to the things that make your community unique. Because such things are not always easy to identify, I’d like you to think for a moment about the Declaration of Independence and try to envision it.

What comes to mind first? If you’re like many people, including me, you’ll probably think about John Hancock’s signature, prominently centered below the main text. Immediately recognizable, it is big, bold, and distinctive, demanding attention among the signatures of his numerous eminent colleagues.

Like human beings, communities also have unique “signatures” or what I’ve come to think of as “signature elements.” While it’s not always as immediately evident as John Hancock’s signature is on the Declaration, a community’s signature is rooted in its unique history, people, arts, architecture, heritage, natural resources, culture, commerce, agriculture, industry, and institutions. The endlessly varying combinations of these diverse elements mean that no two places are exactly alike.

Signature elements therefore help differentiate communities from one another and can be a continuous source of pride, inspiration and creativity. Like abundant water or electrical power, coal, timber or iron, they are a form of raw material and often serve as building blocks which communities can use to tell their stories, stimulate revitalization and growth and promote themselves to potential residents, visitors, and investors.

Communities use their signature elements in a variety of ways. For example:

Lyons, New York has based its main street revitalization efforts on its connection with New York State’s Erie Canal system and the H.G. Hotchkiss International Prize Medal Essential Oil Company, which produced peppermint and other essential oils and brought global attention to the village for many years.

Lyons, New York has based its main street revitalization efforts on its connection with New York State’s Erie Canal system and the H.G. Hotchkiss International Prize Medal Essential Oil Company, which produced peppermint and other essential oils and brought global attention to the village for many years.

Lyons calls itself “the Peppermint Village,” celebrates all things peppermint in a variety of themed events, and tells its canal story in a series of highly descriptive murals and interpretive signs throughout downtown.

Spillville, Iowa identifies itself as the most historic Czech village in America and the oldest Bohemian community north of St. Louis and west of the Mississippi River.

Signature elements include its peaceful rural setting, the large, intricately carved clocks produced by the Bily brothers, an association with the Czech composer Antonin Dvorak, and a large collection of cast-metal grave markers designed by Charles Andera and found in cemeteries throughout the U.S.

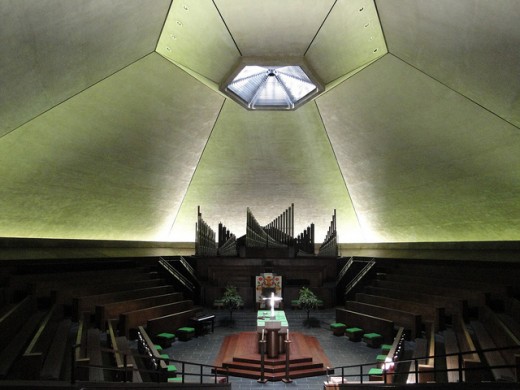

Columbus, Indiana has established itself as a mecca for enthusiasts of modern art and architecture, celebrating more than 70 buildings and works of public art by numerous internationally recognized architects and artists. For an overview of some of the remarkable buildings in this mid-sized city, see this six minute video narrated by Charles Osgood from the CBS Sunday Morning show (May 22, 2011).

Similarly, Oak Park, Illinois stands out among its neighbors for its concentration of buildings designed by Frank Lloyd Wright;

Salem, Massachusetts is well known for its association with witches as well as its historic architecture, maritime heritage and art. And, when thinking about the state of Kentucky, most of us would immediately identify horse racing, blue grass and bourbon as signature elements!

As these examples should make clear, signature elements manifest themselves in specific local and regional products, places, events, and activities such as architecture in Oak Park, Illinois; wild rice in Minnesota; maple syrup in Vermont; Hatch chili peppers in New Mexico; or in music such as the blues in Chicago and country music in Nashville. They spring forth from unique characteristics of places and the people that live, work, create, and do business in them.

All of this is important because community planners and economic development professionals are increasingly identifying communities’ signature elements, or more precisely, location specific history, heritage, historic sites and architecture, museums, arts, culture, and design, as well as the businesses, industries, and institutions related to these things, as key elements of what has become known as the creative economy. To tap into this segment of the economy, communities are turning increasingly to cultural economic development, which includes, among other things, historic preservation, main street revitalization, and heritage tourism.

Regardless of their size or sophistication, areas that are achieving the most substantial benefits from cultural economic development, including municipalities, regions, states, and nations, have based their efforts on thoughtful planning, organization, collaboration and strategic investment.

Their efforts have often begun with an inventory and analysis of existing conditions and the identification of opportunities and threats relating to the creative/cultural economy. This has usually been done as part of a larger, long-range planning process, including preparation of comprehensive plans or downtown revitalization strategies, or as part of more focused, issue-specific plans such as historic resource surveys, historic preservation plans or cultural plans.

Depending on the size of the area and the extent of issues being studied, these efforts have been overseen and directed by local officials and/or staff, individual consultants, or teams of specialized consultants.

With these things in mind, my next post will provide you with a brief overview of each of these types of plans, describing their purpose, key elements, and preparation. It will be followed by several posts that will focus on how communities organize to plan, whether historic preservation can help your community, whether historic preservation presents obstacles or opportunities, and the benefits of historic preservation. These posts will set the stage for more detailed discussion of specific preservation tools and strategies, after which we will broaden the subject to focus on other aspects of cultural economic planning and development.

To end today, let’s return to the questions I asked you to think about. What are your community’s signature elements? Is your community making use of them yet, and if so, how? Has your community engaged in any type of historic preservation or cultural planning?

Amy Facca is a historic preservation planner, architectural historian, and grant writer with a strong interested in cultural economic development. Facca has joined the PlannersWeb as a contributing writer. She previously authored An Introduction to Historic Preservation Planning for the Planning Commissioners Journal.