See also Editor Wayne Senville’s follow up discussion with Beth Humstone about her article.

Read an excerpt from this article below. You can download the full article by using the link at the end of the excerpt.

Just as walls once created clear distinctions between town and countryside, today’s urban containment strategies aim to keep urban places urban and rural places rural. Urban containment — the constraint of growth to limited geographic areas — is of great interest to planners for its potential benefits of preserving open space, saving money on public services, reinvesting in cities, and providing a more predictable permitting process. In fact, the American Planning Association estimates that over 100 metropolitan areas now have some form of urban containment strategy.

Of the three principal kinds of urban containment strategies — urban service areas, greenbelts, and urban growth boundaries — in this article, we’ll be focusing on urban growth boundaries.

What is An Urban Growth Boundary?

An urban growth boundary encompasses an area defined on a map where:

— development is permitted at a higher density or intensity than surrounding areas,

— mixed uses are typically encouraged, and

— a full complement of public services is provided.

The size of the area within the boundary typically is configured to provide sufficient land to meet population and land use needs for a 20-year period. Over time, the boundaries may be adjusted — either by expansion or contraction — to meet changing conditions. In the United States, urban growth boundaries have been established through local initiatives, regional strategies, and state mandates and/or incentives.

Why Plan for Urban Growth Boundaries?

Communities and regions plan for urban growth boundaries in order to meet the goals of their comprehensive plans, because they are mandated or encouraged to do so by state government, or because they have a particular need such as revitalization of a downtown or protection of important farmland.

Within a comprehensive plan, places are delineated both where growth will be encouraged and development limited. The plan typically contains projections for population, employment, and housing so the community knows how much land is needed for different uses. The plan also identifies existing development, the location and capacity of services, and important environmental and natural resource features.

By designating a growth boundary, a community or region can provide for infill and contiguous growth that reinforces and reinvests in existing settled areas, limits urban services to avoid costly extensions to rural areas, and protects environmental or natural resources outside the center. A few examples:

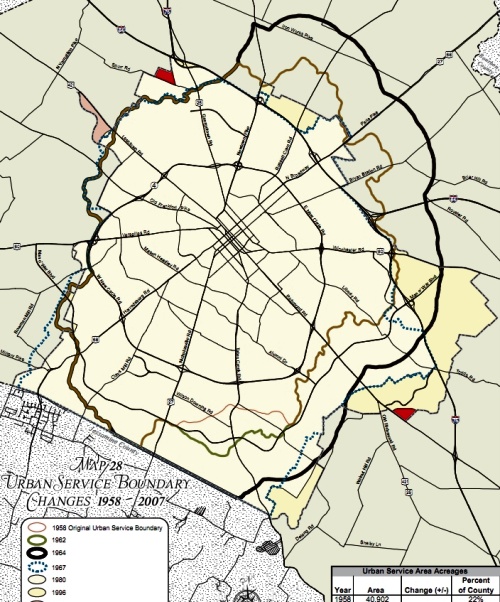

Lexington, Kentucky uses an urban growth boundary to meet its planning goals. The Lexington urban growth boundary, which includes Fayette County, was first adopted in 1958 — the oldest growth boundary in the United States. Its primary purpose was to protect the bluegrass and horse farms for which the region is famous by requiring most development to take place within the boundary and severely limiting development outside the boundary.

Over the years, the boundary has been adjusted, and planning and zoning for the area has been altered to meet changing needs and political pressures. The urban growth area was initially 67 square miles (comprising 22 percent of the county’s total land area); it is now 75 square miles (30 percent).

In New Jersey, the State (in conjunction with the National Park Service) established the Pinelands National Reserve in 1979. Within the 1.1 million acre Reserve, a comprehensive management plan guides the management and protection of environmentally sensitive and agricultural lands threatened by sprawling land development. A joint county-state-federal Pinelands Commission reviews local ordinances for consistency with the management plan.

The plan also delineates regional growth boundaries. The Commission uses a transfer of development rights (TDR) program to protect important open space and natural areas, as well as encourage more development in Pinelands’ town and village centers. To date, over 58,000 acres have been protected and nearly 4,500 development rights have been transferred to projects proposed within “Regional Growth Areas.”

… article continues with discussion of six key planning issues that need to be addressed when considering urban growth boundaries.

Beth Humstone works as a planning consultant on a wide range of projects in rural communities and small towns. She is an advisor to the National Trust for Historic Preservation; former Executive Director of the Vermont Forum on Sprawl (now Smart Growth Vermont); a past member of the Burlington (VT) Planning Commission; and former Chair of Vermont’s Housing & Conservation Trust Fund Board.

Humstone is co-author, with Julie Campoli and Alex MacLean, of Above and Beyond, Visualizing Change in Small Towns and Rural Areas (APA Planners Press, 2002).

You must be logged in or a PlannersWeb member to download this PDF.