A Regional Transit Vision

• North Carolina Triangle region’s population is growing — one million more residents are expected by 2040. 1

• The region is sprawling into undeveloped land outpacing the increase in population.

• Peak hour traffic congestion along major highways is increasing.

• A significant percentage of residents commute across county lines to dispersed job centers. Key among them are Research Triangle Park, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and Duke University.

• Many people who do not drive or own cars find their travel options limited.

These are some of the challenges facing Triangle residents and planners today.

The long awaited Triangle Transit Plan envisions a regional transit system to meet the mobility needs of 1.6 million residents … mitigate congestion, and offer transportation choices.

In 2009, area Metropolitan Planning Organizations adopted the comprehensive, multi-modal 2035 Long Range Transportation Plan to address current and future transportation challenges, including regional transit.

The long awaited Triangle Transit Plan envisions a regional transit system to meet the mobility needs of the Triangle 1.6 million residents (expected to grow to 2.9 million by 2040), mitigate congestion, and offer transportation choices for all Triangle residents, now and into the future.

The Regional Transit Plan 2 for Orange, Durham and Wake Counties includes:

1. Expanded bus service throughout the region including Sunday service from Chapel Hill to Durham, Research Triangle Park, Raleigh-Durham Airport, and Raleigh.

2. Regional light rail and commuter rail service will anchor the system connecting the region’s principal centers of activity.

3. Transit circulators will create connections with expanded local and regional bus and rail services.

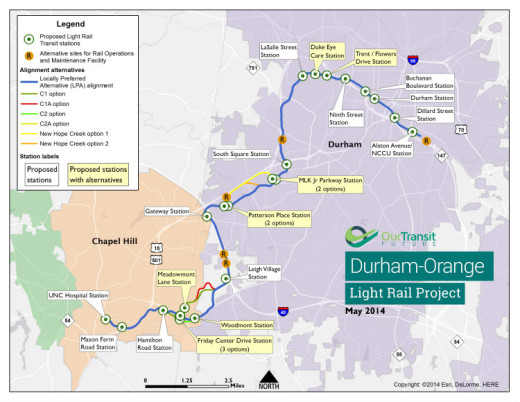

Triangle Transit, the authority in charge of the regional transit plan, has begun to roll out expanded bus service and to develop the 17.1 mile Durham-Orange Light Rail (D-O LR) from the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill to Duke University and North Carolina Central University in Durham. The D-O LR will connect educational, medical, employment, and mixed use communities, offering an alternative travel corridor for the “at capacity” highways serving these destinations.

Initial projections for 2035 indicate ridership will exceed 12,000 boardings per day.

3

Two other transit proposals in the pipeline are the 37 mile Durham-Wake Corridor Commuter Rail Line from the Duke Medical Center in Durham, to the Research Triangle Park (RTP), Cary and Raleigh; and the Wake County Corridor Light Rail Line from RTP to Downtown Raleigh and Triangle Town Center.

However, both projects are on hold until Wake County moves forward with a transit plan.

Triangle residents are already using existing local and regional bus routes more and driving less. “Ridership in 2013 was 1,769,200,” said Triangle Transit communications officer Brad Schulz. “Between fiscal year 2010 and 2013, Triangle Transit had over 30 months of double digit monthly increases.” 4

The numbers augur well for future transit investment.

Some Questions for the Triangle Transit Plan

While the regional transit plan is a necessary component of regional growth and has popular support, some planning experts have questioned the role of transit in reducing traffic congestion and the efficacy of light rail in a sprawling land form with several jobs clusters and few dense residential and mixed used neighborhoods.

Also, with the signing of the Strategic Mobility Formula, the state’s new transportation funding model for all modes of transportation, state funding for light-rail and commuter trains may be in jeopardy if funds are prioritized toward highways and freight railroad over transit.

Is Transit the Answer for Congestion?

Conventional wisdom has it that transit reduces congestion. But is that true?

Conventional wisdom has it that transit reduces congestion. But is that true?

Eric Lamb, Manager of the City of Raleigh Office of Transportation, is not so sure about the correlation between transit and congestion abatement. 5 He cites South Boulevard in Charlotte which directly parallels that city’s Lynx Blue Line light rail system. Despite the light rail line carrying 15,000 passengers per day, there has been no corresponding reduction in traffic volumes along South Boulevard.

What transit systems can do … is help minimize the amount of new traffic and create high density transit-oriented developments which require fewer drive trips.

What transit systems can do, Lamb says, is help minimize the amount of new traffic and help create high density transit-oriented developments which require fewer drive trips than conventional developments and are “vital for good growth and positive economic development.”

As transit planning consultant Jarrett Walker explains, transit raises the level of economic activity, at a fixed level of congestion. 6 Specifically, traffic congestion in a city with no transit discourages travel, which then translates into a cap on economic activity. But, if a city is supported by transit, walking, and cycling options that enable people of all ages, incomes, and backgrounds to travel, economic activity and prosperity can continue to grow while congestion remains constant.

As discussed in Walker’s article, Toronto is an example of a city whose downtown has grown significantly as an employment hub — despite continued traffic congestion — because its transit service has continued to expand.

Rail Transit in a Suburban Land Form?

Are light rail and commuter rail appropriate for suburban land forms?

John Pucher, a professor in the Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy at Rutgers University, thinks light rail and commuter rail are justified in Orange and Durham counties where there are: more walkers and bicyclists; a favorable route between the cities; and tight parking around the three Universities. 7

In contrast, Pucher notes that for highly diffuse and decentralized Wake County, bus rapid transit using high-occupancy vehicle lanes on area highways, would be more efficient, flexible, and cost-effective than rail systems.

A panel of transportation experts advised Wake County leaders to go slow on commuter and light rail service … Instead, they called for providing better bus service.

A panel of transportation experts likewise advised Wake County leaders to go slow on commuter and light rail service, citing region size, high costs, and low ridership. Instead, they called for providing better bus service. 8

A report commissioned by the John Locke Foundation, a conservative think tank, also found the proposed commuter and light rail inappropriate for Wake County given its size and density, questioning ridership and occupancy estimates and the appeal of transit trip time longer than drive time for the same trip. 9

In a letter to the Editor, Wake County Commissioner Paul Coble cautioned that Wake County “take careful and deliberate steps, with any final plan meeting tests of availability, reliability and affordability … Rail at any cost does not address all of our needs.” 10

Wake County officials have thus far held off on a final commitment to the Wake County Rail Line concerned over not overpromising what they can deliver.

Will Transportation Funding Priorities Favor Transit?

North Carolina’s Strategic Mobility Formula, a new way to fund and prioritize transportation, has allocated $450 million among seven regions for highways, ferry, rail, airport upgrades, and transit. Bruce Siceloff, transportation reporter for the News & Observer notes that “…. roads are certainly favored over transit with at least 90% of the construction money set aside for roads and bridges, at least 4% for transit and other non-road projects. In between is 6% that can go either way.” 11

How then will the Durham-Orange Light Rail, estimated to cost $1.35 billion, be funded? The local sales tax increase approved by Orange and Durham county voters will cover 25% of the cost and the project assumes 25% and 50% of state and federal funding respectively. Although the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) has approved the project, federal participation will be decided only after the environmental study is completed. Triangle Transit with work with NCDOT and state legislatures to secure state funding at a later date. 12

While there is a reasonable expectation of federal and state funding, neither is guaranteed.

Triangle Future is Linked to Land Use and Transit

Urban “metros” are the engines of economic prosperity in this century.

Urban “metros” are the engines of economic prosperity in this century, pointed out Bruce Katz, Vice President of the Brookings Institution, in a talk in Raleigh. 13 This synergy, Katz said, can happen only if the Triangle reins in sprawl by connecting the cities with mass transit. Otherwise, he warned, the Triangle will lose out to bigger, better-planned, and more “efficient” regions with a higher quality of life.

Triangle counties, cities, and towns must transform their land use patterns to accommodate greater density, connectivity, and uses. Triangle Transit is attempting to do just that — take people to existing communities and job centers — and create new routes, stations and infrastructure to spark additional development and meet future growth.

Bumps in the road and all, hopes are high the Regional Triangle Transit Plan will move forward.

Deepa Sanyal is a Community Planning consultant and Training Professional. She provides professional services to local governments, communities, universities, and civic organizations seeking guidance on comprehensive planning, community assessments & revitalization, historic preservation, and cultural tourism. Deepa also advocates for and writes about sustainable development issues, and serves on the Chatham County Planning Board in her “Corner of the Triangle.”

Notes:

- See graphic on Capital Area Friends of Transit web site. ↩

- The Regional Transit Plan. ↩

- The Durham County Bus and Rail Investment Plan, p. 6 (DCHC MPO, Triangle Transit Board of Trustees, and Durham Board of County Commissioners; adopted June 2013). ↩

- Reported by Dawn Kurry in “Why more Triangle motorists are using public transit” (Triangle Business Journal, Dec. 6, 2013). ↩

- Email from Eric Lamb to Deepa Sanyal, May 29, 2014. ↩

- Jarrett Walker, “What does transit do about traffic congestion?” (Human Transit blog, July 2010). ↩

- “Planning expert: Raleigh not suited for light rail” (WRAL.com, March 15, 2013). ↩

- Bruce Siceloff, “Wake County Isn’t Crowded Enough to Support Rail Transit, Experts Say” (Newsobserver.com, Nov. 12, 2013). ↩

- Review of the Wake County Transit Plan (John Locke Foundation, Jan. 31, 2012). ↩

- Paul Coble, “Developing a Reasonable, Sustainable and Practical Transit Plan” (Letter to the Editor, News & Observer, Feb. 11, 2014). ↩

- Email from Bruce Siceloff to Deepa Sanyal (May 29, 2014). ↩

- Email from Brad Schulz to Deepa Sanyal (June 4, 2014). ↩

- Reported by Bob Geary in “The Triangle is growing apart, separated by geography, politics, transit and identity” (Indy Week, Mar. 5, 2008). ↩