Read an excerpt from this article below. You can download the full article by using the link at the end of the excerpt.

Read start of Amy Facca’s article, “An Introduction to Historic Preservation Planning”

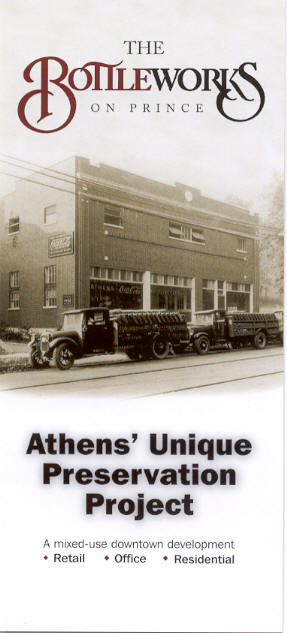

Across the country there are signs of a renewed interest in our communities’ historic resources. Abandoned, vacant, and underutilized historic buildings are being converted into distinctive, mixed-use venues combining retail, residential, and office uses. Neglected, but once spectacular, theaters are being restored as new performance spaces. Historic residential districts and neighborhoods are being reinvigorated. As these transformations take place, historic preservation is being seen as providing tangible benefits to communities large and small.

Many of us have taken time to visit places noted for their historic character, whether larger cities like Savannah, Georgia; San Antonio, Texas; or New Orleans, Louisiana, or smaller communities like Natchez, Mississippi; Virginia City, Nevada; Port Townsend, Washington; and Quincy, Illinois. Virtually every one of us has undoubtedly spent time pleasantly walking through historic Main Street and residential districts. The appeal of these areas is universal.

Reflecting this, a growing number of communities have been incorporating historic preservation into their comprehensive plans, downtown revitalization strategies, and neighborhood improvement plans.

Reflecting this, a growing number of communities have been incorporating historic preservation into their comprehensive plans, downtown revitalization strategies, and neighborhood improvement plans.

This article is intended to provide a brief introduction to historic preservation planning. You’ll read about some of the benefits of preservation, and find information on how communities are implementing local preservation policies. Resources are also listed for those of you who want to learn more about preservation planning.

Preservation in America

The first interest in preserving historic structures can be found in the mid-19th Century efforts to acquire and restore the homes of famous Americans like George Washington’s Mount Vernon and Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello. Beginning in 1927, the scope of historic preservation expanded dramatically with the start of John D. Rockefeller’s restoration of Williamsburg, colonial Virginia’s capital city. The next, and perhaps most important, step in the preservation movement was taken in 1931 when Charleston, South Carolina, established the nation’s first local historic district. Preservation no longer concerned itself just with individual structures, but also took into account the historic value of groups of buildings, districts, and even whole communities.

As planning historian Larry Gerckens has noted, “The demolition of New York City’s Pennsylvania Station in 1965, one of the nation’s most magnificent railroad stations, shocked many New Yorkers, as well as citizens across the country. Outraged by the fact that there was no legal recourse to stop the demolition (the building was privately owned by the nearly bankrupt Pennsylvania Railroad), New Yorkers responded by enacting later that year a comprehensive landmarks preservation law.” See “H is for Historic Preservation.”

Historic preservation became federal policy with the adoption of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) in 1966. Sidebar: National Historic Preservation Act. This law was enacted following completion of With Heritage So Rich, a comprehensive report undertaken by the U.S. Conference of Mayor’s Special Committee on Historic Preservation in response to the substantial loss of historic and cultural resources brought about by urban renewal and construction of the interstate highway system.

Among other things, the NHPA authorized creation of a National Register of Historic Places, directing the U.S. Secretary of Interior to maintain a list of districts, sites, buildings, structures, and objects significant in American history, architecture, archeology, engineering and culture. Indeed, within twenty-five years of its passage there were over 8,000 historic districts listed in the National Register.

The NHPA also authorized the establishment of historic preservation offices in each state, and mandated the creation of standards and guidelines for various preservation activities, such as how to identify historic resources. The survey process and criteria for evaluating potential historic resources are important components of preservation planning because they help to distinguish what is historic from what is merely old. Sidebar, Identifying Historic Resources.

In recent years, historic preservation has continued to expand its focus, with new interest on preserving and enhancing the distinctive character of communities, and even regions.

Benefits of Historic Preservation

Since the 1970s, mounting evidence has shown that historic preservation can be a powerful community and economic development strategy. Evidence includes statistics compiled from annual surveys conducted by the National Trust for Historic Preservation and statewide Main Street programs, state-level tourism and economic impact studies, and studies that have analyzed the impact of specific actions such as historic designation, tax credits, and revolving loan funds. Among the findings:

- Creation of local historic districts stabilizes, and often increases residential and commercial property values.

- Increases in property values in historic districts are typically greater than increases in the community at large.

- Historic building rehabilitation, which is more labor intensive and requires greater specialization and higher skills levels, creates more jobs and results in more local business than does new construction.

- Heritage tourism provides substantial economic benefits. Tourists drawn by a community’s (or region’s) historic character typically stay longer and spend more during their visit than other tourists.

- Historic rehabilitation encourages additional neighborhood investment and produces a high return for municipal dollars spent.

- Use of a city or town’s existing, historic building stock can support growth management policies by increasing the availability of centrally located housing.

Planning for Historic Preservation

Elected and appointed officials often face difficult and controversial decisions that affect the character of their communities. Many of these decisions relate to older and historic buildings, neighborhoods, and commercial districts. Examples include:

- Demolishing an old building or group of buildings to make way for new development such as a chain drugstore or “big box” retailer.

- Constructing a new addition on an existing building.

- Constructing a new building in an older neighborhood.

- Replacing historic building elements such as windows, doors, porches, roofs, or original siding materials.

When making these decisions, elected and appointed officials look to their community’s long-range plan, zoning ordinances, and related land use regulations. In many communities, these documents provide little guidance in terms of historic preservation. While plans or ordinances may reference (often in an appendix) those buildings or neighborhoods listed in National and State Registers of Historic Places, this information, in and of itself, is of minimal value to decision makers. Without more, simply being listed in the National or State Registers only provides limited protection from federal or state actions that may adversely affect historic resources.

Preservation planning is key to establishing public policies and strategies that can help prevent the loss of historic resources. It provides a forum for community discussion and education about issues related to historic resources and development. This includes important questions such as when and where it may be appropriate to demolish historic buildings, and what resources must be protected to maintain the community’s unique historic and architectural character. …

End of excerpt

The article goes on to discuss: preservation plans; preservation ordinances; enhancing historic resources; educating the public; and sources of assistance.

Also included in this download are the following articles:

- Historic Preservation Is Smart Growth, by Donovan Rypkema

- Historic Preservation Ordinances: Frequently Asked Questions, by Julia Miller, Esq.

- Preservation Takes Center Stage, by Wayne Senville

- Preservation Boosts Local Economies, by Edward McMahon

You must be logged in or a PlannersWeb member to download this PDF.