with a response from Jennifer Wallace-Brodeur

Editor’s Introduction: this is the second of a monthly, year-long series focusing on issues facing both younger and older generations. Two talented individuals — Jennifer Wallace-Brodeur and Stuart Andreason — will be providing you with their perspectives. Jennifer is a senior advisor with AARP, while Stuart is a young planner and PhD student with a wide range of research interests (you’ve already heard from Stuart in two articles about “MOOCs”).

We hope you’ll engage in a discussion with the authors by using our LinkedIn group page. If you’re not a member, you can join LinkedIn at no charge and then participate in our group. Hope to see you there!

Could your community or local businesses benefit from passionate, smart, and well-educated workers who are willing to work long hours for somewhat lower pay than their equally skilled peers?

If that pitch isn’t enough alone, what if these workers were also interested in authentic communities, walkable commercial areas, and had a high disposable income? If any of these character traits are of interest to your community, then you have probably considered or are working to attract young college graduates to your town or city.

Attracting young adults is a challenge for any community and citizen planners face what may seem like a chicken and egg question related to getting more young people to live in their communities. The question is, “Should we invest in creating jobs or in quality of life to encourage young people to move to our community?” In reality, communities need to invest in both.

The Pew Partnership for Civic Change [full disclosure: I used to work for the organization] developed the Thriving Communities Database that showed improvements in the economy or quality of life tracked together. Because of the close relationship, I’ll discuss both, but this month will focus on jobs for young adults.

Challenges for Young College Graduates in the Labor Market

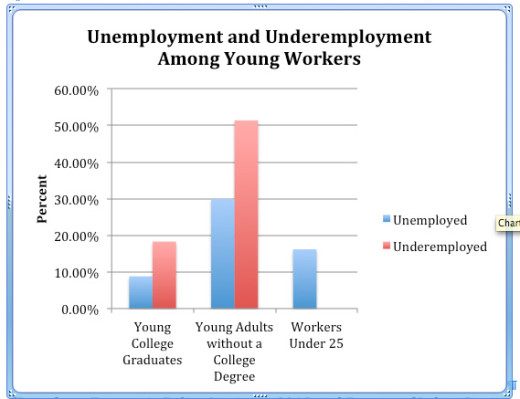

Like most workers during the current recession, young graduates face significant difficulty finding work that meets their skills. The Economic Policy Institute recently showed that 18.3 percent of recent college graduates were either unemployed or underemployed (working in a job that was below or outside of their skill set). 1

College graduates are highly mobile and when they aren’t able to find a job that matches their skills they are likely to leave the community, often referred to as “brain drain.”

Combating Brain Drain

Communities can encourage young adults to stay in the area (or return to their hometown) after they graduate. Below are a number of ways that communities have encouraged college graduates to stay through connecting young adults to jobs.

One of the best ways to combat college graduates leaving the community is to work to connect them with employers who are in their field and might ultimately hire them.

Internships – One of the best ways to combat college graduates leaving the community is to work to connect them with employers who are in their field and might ultimately hire them. A study of Pittsburgh graduates found that those who held internships with or had worked for local companies were more likely to stay in the community after they graduated. 2 Internships helped students figure out what types of local industries had jobs and the skills that they needed to get those jobs. Companies and organizations often hired their interns to full time jobs after graduation as well.

Cooperative Programs with Colleges and Universities – the Research Triangle Park, an industrial park with a high concentration of life science firms, in North Carolina partnered with local community colleges to target training at the institutions to the needs of firms in the area. This prepared workers to be employable and ready for the jobs that were available in the area. It also made companies expand locally (and less likely to leave) because there were talented workers ready for the jobs. 3

While many places do not have a high concentration of life science businesses, most places do have a specialty in some type of business or industry that has some specific training needs. The North Carolina example can be replicated by connecting with local businesses, universities, and the local economic development agencies to start conversations that identify local industries that need workers and the college training that can be helpful.

Target Certain Students – the Pittsburgh study noted above also found that students who attended high school or grew up in the Pittsburgh area were more likely to stay than leave. This could be because they had family ties, friends, and a history in the area. A connection to a place can encourage a young graduate to stay over the job prospects in a different or distant community, but the graduate will still need a job that meets their education. They also might not know what types of jobs will be available in their hometown.

Teaching these young adults, even as early as middle school, about the local economy can help them identify careers and education that are conducive to staying local. This early education about career opportunities also helps encourage young students to apply themselves in middle and high school and can improve achievement and graduation rates. 4

Involve Young Adults – communities across the country are starting young professional networking groups. Sometimes these organizations are an offshoot of a local chamber of commerce or business network that focus specifically on involving young professionals. Other organizations, like Campus Philly, are formed specifically to engage students in finding local jobs (and to promote the local quality of life).

The Role of Planning Commission and Citizen Planners

The policy objectives above may seem to push the boundaries of what planning commissions and citizen planners traditionally do, but they can be vital players in coordinating efforts and developing plans to increase job opportunities for young adults. A number of communities across the country have created youth master plans — addressing the needs of children and young adults.

Citizens and political leaders in Nashville created a plan titled “14 For Our Future,” a youth master plan that outlines goals for children and young adults, including job preparedness, educational support, and training for careers in the area. Like any quality comprehensive plan, it takes a broad look at youth needs in the community and also covers educational reform, safety, health, and quality of life for youth. The plan came as a result of a long planning and community engagement process.

The late Jack McCall, in a 1997 Planning Commissioners Journal article, “Education and Economic Development,” showed that high quality local education is key to bringing businesses to a community. McCall pointed out that an important part of this is working with schools to identify how business and schools can compliment each other — and that many communities have established advisory committees to guide the business-education relationship.

Those involved in the traditional planning of a community are key to these types of committees because of their broad views and understanding of the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and upcoming challenges in the area.

Summing Up:

The examples above show that linking young adults to the local employment must incorporate local knowledge and innovation to meet the context of the local economy. Active collaboration between citizen planners, local educational institutions, industry, economic development planners, and young adults is common across each example too. Nashville’s youth master plan involved these community members. Envision Utah, a regional planning organization in Salt Lake City identifies broad involvement in economic development planning (for communities young or old) as a key first step in achieving quality job growth.

Young college graduates are a boon to local businesses because they work hard and bring new ideas. Coupled with sound planning investments (to improve quality of life) these job related initiatives can encourage young graduates to locate in your community.

Stuart Andreason is a doctoral candidate in the Department of City and Regional Planning at the University of Pennsylvania where he studies community and economic development. He previously researched civic innovation in community participation.

Prior to entering graduate school, Stuart worked as the Executive Director of a Main Street Organization, the Orange Downtown Alliance, in Orange, Virginia.

A Response from Jennifer Wallace-Brodeur:

It is imperative that local leaders and planners be aware of and have a strategy to make the most of the talent and experience of older workers and entrepreneurs.

Stuart rightly points out the need to provide opportunities for young people in your community. At the same time, it is imperative that local leaders and planners be aware of and have a strategy to make the most of the talent and experience of older workers and entrepreneurs.

Let’s look first at entrepreneurs. According to the 2013 Kauffman Index of Entrepreneurial Activity, “the share of new entrepreneurs ages 55-64 grew from 14.3% to 23.4% from 1996 to 2012. The oldest age group (ages 55 to 64) experienced a rising share of all new entrepreneurs, mainly because it represents an increasing share of the population.” 5 Many boomers are looking at starting a business as an “encore” career — an opportunity to pursue a lifelong passion.

According to “Staying Ahead of the Curve 2013: AARP Multicultural Work and Career Study,” 6 10 percent of workers ages 45-74 who are current wage and salary workers say they plan to start a business once they retire. They often have the financial resources to survive a business start-up and have a lifetime of experience from which to draw.

Community strategies to attract or support entrepreneurs of all ages include good infrastructure and high-speed Internet access, high quality-of-life, affordable housing options near work, availability of low-cost incubator space, and a group of peers with whom to interact. With greater awareness about the desires and opportunities for entrepreneurship among older residents, your community can have a more intentional and strategic plan to attract and support this population of job-creators. Ideally, innovative strategies will emerge to specifically encourage and attract older business owners.

Understanding the demographics of your community’s workforce and how it is aging is also important. Many people are working longer and delaying retirement, either out of necessity or because of a desire to stay engaged in the community.

Older workers should be recognized as an important asset as communities work to lure businesses.

Planners can address issues important to older workers (and workers of all ages) through planning and land use decisions. Key considerations would include how workers will access jobs as they get older. Are there transportation options to employment centers? Can workers find affordable housing near their jobs? Is it easy for businesses to locate in downtowns linking housing, transportation, services, and work?

If your community is interested in a process to plan for aging, the AARP Network of Age-Friendly Communities program offers a framework from which to engage the community and develop an action plan. Within this framework, employment is one of the eight issues a community must address to be age-friendly.

Jennifer Wallace-Brodeur has been at AARP since 2005, serving as Associate State Director in the Vermont State Office until 2013, and then moving to the national office as Senior Advisor States. In Vermont, she led the Burlington Livable Community Project, which established a vision and action steps for Burlington to meet the needs of its aging population. This was one of AARP’s first local livable community projects. She also led AARP’s campaign to pass Complete Streets legislation in 2011, which earned her the Outstanding Service Award from the Vermont Planners Association.

Jennifer is active as a community volunteer, currently serving on the Burlington Planning Commission and previously as chair of the Burlington Electric Commission. In 2012, she was appointed to the Governor’s Commission on Successful Aging and served as chair of the livable communities subcommittee.

A Reply from Stuart Andreason:

Jennifer’s reaction to the article highlight what I anticipate will be a common theme in the “Across Generations: Young and Old” series — that good planning, development, and economic change benefit many constituencies and one of the best ways to approach planning is to focus on multiple generations and creating connections between them.

Young adults may have unique difficulties in finding work and seniors may have somewhat different challenges as they prepare to retire or move into a second “retirement” career or entrepreneurial venture, but many challenges are similar and improvements for one age group can benefit the other.

Planners and citizen planners may target one of these age groups, but building a network of businesses, entrepreneurs, and workers across generations is a tried and true strategy. Comprehensive, multigenerational strategies to community challenges in job creation work. I anticipate that this is also true in other arenas like transportation and housing.

A Note from PlannersWeb Editor Wayne Senville:

One other way of bridging the generational divide is through mentorship programs. I personally benefitted from the nonprofit SCORE program 22 years ago when starting up the Planning Commissioners Journal. Score connected me with a local retiree with substantial business experience. We met several times, and I gained some great ideas — and was alerted to some potential pitfalls — in getting the Planning Commissioners Journal off the ground.

If you’re a retiree, see if there are ways of helping the next generation of business people by giving some of your time, and sharing what you’ve learned. If you’re looking to set up your first business, check out Score or similar programs in your area and see about connecting with someone who can offer some guidance.

Notes:

- The same report notes the grim situation for young adults without a college degree. 29.9 percent are unemployed and 51.4 are underemployed. ↩

- Hansen, Susan B., Carolyn Ban, and Leonard Huggins. 2003. “Explaining the ‘Brain Drain’ from Older Industrial Cities: The Pittsburgh Region.” Economic Development Quarterly 17 (2) (May 1): 132 –147. ↩

- Lowe, Nichola J. 2007. “Job Creation and the Knowledge Economy: Lessons From North Carolina’s Life Science Manufacturing Initiative.” Economic Development Quarterly 21 (4) (November): 339–353. ↩

- Symonds, William C., Robert B. Schwartz, and Ronald F. Ferguson. 2011. “Pathways to Prosperity: Meeting the Challenge of Preparing Young Americans for the 21st Century”. Boston: Pathways to Prosperity Project, Harvard Graduate School of Education. ↩

- Fairlee, R. W. (2013). Kauffman index of entrepreneurial activity 1996-2012. Kansas City, MO: Kauffman Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.kauffman.org/uploadedFiles/KIEA_2013_report.pdf ↩

- Staying Ahead of the Curve 2013: AARP Multicultural Work and Career Study ↩