Read the start of this article below; to view full article you need to be a PlannersWeb member. Already a member? — be sure you’re logged-in. Not a member? Consider joining the PlannersWeb.

In my last column I spoke about how meaningful engagement strategies are needed if we’re to break through the mistrust that too often comes between citizens and local government bodies (including planning commissions). As I noted, a growing number of those of us who work in the field of civic participation have started to think about public engagement as comprising a range of potential strategies that build on each other. The aim is to create a more comprehensive and useful conception of public engagement than the “hold-a-meeting-and-listen-to-people-complain” approach we have so often felt stuck with.

My framing for this is simple: Tell, Ask, Dialogue, Collaborate.

Here’s what I mean:

Tell. We are Telling something to (or at) the public when we give them information. We tend to do this more than anything else — partly because we are dealing with complex issues and want people to know at least some of what we know, and partly because it’s a heck of a lot easier for us to lecture than to engage you in figuring out yourself what the information means and why it matters to you. This is why teachers and professors resort to lectures.

Tell. We are Telling something to (or at) the public when we give them information. We tend to do this more than anything else — partly because we are dealing with complex issues and want people to know at least some of what we know, and partly because it’s a heck of a lot easier for us to lecture than to engage you in figuring out yourself what the information means and why it matters to you. This is why teachers and professors resort to lectures.

When your goal is to stick a set of information in someone else’s head, Telling is the quickest way to do it. But it’s also the least effective — psychologists have pretty well proven that people retain only a small proportion of what they hear or read, especially compared to their retention and comprehension when they have actually worked with the information themselves.

Ask. We also Ask people for their opinions or experiences a lot. We Ask survey questions like “where do you buy your groceries” or “would you support a proposal to rezone this property?” And we Ask “do you like this land use scenario or that land use scenario better?” Asking is an information-seeking activity — it’s trying to uncover facts that we can use to make a better-informed decision (“better informed” in your context might mean “more factually accurate,” or “more politically palatable,” or something else). Asking, if you think about it, is a fundamentally extractive process -– we are getting something we need out of the person we are Asking.

This isn’t all bad by any stretch. Just like we need people to have information to work with, we also need to know what they’re thinking. The problem is that Asking, like Telling, is at best an incomplete part of what we need. Members of the public have the benefit of expressing their opinions, but it’s a limited benefit. When we are done Asking, we say, “thank you for your opinion … goodbye. We’ll let you know when we want to talk to you again.”

As a resident, I have no control over what you do with my feedback. If I end up thinking that you misunderstood or ignored my feedback, I’m likely to conclude that I wasted my time.

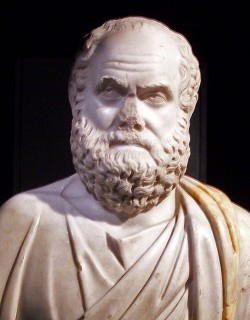

Bust of Socrates, from Garden of Alexandria (Egypt) Antiquities Museum; photo by Sebastià Giralt on Flickr; Creative Commons license

Bust of Socrates, from Garden of Alexandria (Egypt) Antiquities Museum; photo by Sebastià Giralt on Flickr; Creative Commons license

Dialogue. Dialogue is an ancient method (remember Socrates?) for not just building up a body of facts, but creating shared understanding among a group of people.

A dialogue can involve a review of factual information, sharing of opinions, review of alternative options, and so on. But here is the critical element: all of the participants in a dialogue are participating. No one is passive in a dialogue. If people are listening but not speaking, they are an audience to the dialogue, and thus not part of the dialogue at all. The very idea of a Dialogue does not include passive recipients, like Telling and Asking do.

Della Rucker, AICP, CEcD, is the Principal of Wise Economy Workshop, a consulting firm that assists local governments and nonprofit organizations with the information and processes for making wise planning and economic development decisions.

Rucker is also Managing Editor of EngagingCities and author of the recent book The Local Economy Revolution: What’s Changed and How You Can Help — portions of which will be serialized here on PlannersWeb.com during 2014.

You must be logged in or a PlannersWeb member to read the rest of the article.