Read an excerpt from this article below. You can download the full article by using the link at the end of the excerpt.

Think of an older neighborhood with smallish houses set back from tree-lined streets. Then picture a new home, three stories high, pushing to the edge of its lot, towering over its neighbor. Even if the design is right — Craftsman on a street of bungalows — the scale is all wrong. The house looks bloated and out of place. Or maybe three blocks of modern townhouses are built just outside a village of historic single-family homes. Most people know when buildings do not fit their surroundings, but many communities struggle with how to combat such construction proactively.

What’s at stake is a sense of place, which comes as much from a town’s man-made landscape as from its natural setting and the personality traits of its residents. New England’s picket fences, San Francisco’s colorful Victorians — these speak to each area’s character and uniqueness and are part of what attracts people to visit or live there. But what of the street lined with nearly identical garage-fronted homes lacking architectural details and providing no regional clues? That generic street could be anywhere, and for many people that’s a problem.

“A lot of things get done hastily, without people being very aware of what gives a place distinction,” says Philip Langdon, senior editor of New Urban News.

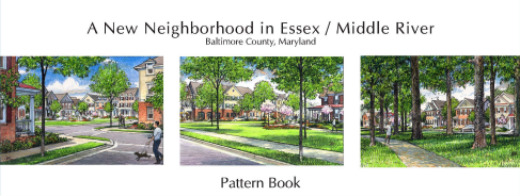

Pattern books filled with historical and architectural data and guidelines can help cities and towns steer development efforts to more easily protect and enhance their identity. Sometimes they contain regulations that must be followed; other times they offer suggestions.

Pattern books have been called a tool for New Urbanism, and though many are used to promote traditional neighborhood design, that is not their only purpose. The push to create a pattern book often comes after a city witnesses out-of-place building — a log cabin in the seaside town of Denton, Maryland, or rebuilt dwellings crowding small lots in Kansas City’s post-World War II suburbs — or after a municipality creates a special redevelopment zone.

Norfolk, a city on Virginia’s southern coast, has experienced extensive infill development and renovation of older homes.

“The houses have character and history, but often lack the modern amenities that support today’s lifestyles,” said Acquanetta Ellis, Norfolk’s assistant director for planning and community development. “We were seeing construction that was not compatible or appropriate and were concerned because it’s devaluing the communities.”

City officials turned to Pittsburgh-based Urban Design Associates (UDA), an architecture and urban design firm, to develop a citywide pattern book. Created as part of Norfolk’s strategic housing initiative aimed at strengthening the city’s neighborhoods and increasing home ownership, the pattern book was intended, in part, to educate residents about the architectural and historic significance of their homes in the context of Norfolk’s neighborhoods and housing patterns. Virginia law does not allow a city to dictate residents’ architectural style choices, Ellis says, but “what we find is if you educate residents about the choices, most of the time they will make better decisions.”

End of excerpt

You must be logged in or a PlannersWeb member to download this PDF.