with a response from Jennifer Wallace-Brodeur

In the previous installments of our Across Generations series, Jennifer Wallace-Brodeur and I have addressed “first places” (housing) and “second places” (work and jobs). This installment will focus on “third places” (places that promote civic society and quality of life) and quality of life issues.

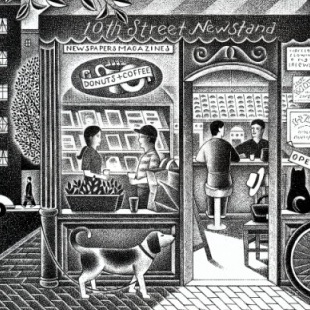

Ray Oldenburg developed the concept of third places in his book The Great Good Place. In it he argues that third places are the foundation of what makes a community vibrant. Third places are often what planners consider quality of life amenities such as parks, cafes, restaurants, and community meeting places (like town halls or schools).

In the decades since the book was first published, quality of life considerations have significantly shifted for young adults as they make decisions on where to live. Planning commissions need to have a quality of life strategy.

What Type of Quality of Life Are Young Adults Demanding

Starting in the 1990s young adults, especially those with a college education, started to change their preferences in relation to where they wanted to live.

An increasing percentage of college graduates between the age 25 and 34 want to live in vibrant neighborhoods or close in walkable suburbs.

An increasing percentage of college graduates between the age 25 and 34 want to live in vibrant neighborhoods or close in walkable suburbs (56 percent of independent Millennials live in cities).[ref]Leigh Gallagher has chronicled this change in her recent book, The End of The Suburbs.[/ref] In fact, in one survey two out of three Millennials said they would prefer to choose a city or neighborhood that fit their lifestyle and then find a job to fit that city and lifestyle.[ref]Joseph Cortright, “The Young and the Restless in a Knowledge Economy” (Slide Presentation at Creative Cities 2.0 Conference, Detroit, Michigan 2008; Slide 16).[/ref] Previous generations let the job drive their location decisions.

Walkable neighborhoods provide easy access to cafes, shops, community centers, parks, transportation, and other community amenities — as well as opportunities to live in more socially and racially diverse social circles.

A 2013 Urban Land Institute survey found that:

“Of the three major generations … (Gen Y, Gen X and Baby Boomers), Gen Y [i.e, Millenials] — the largest generation, the most racially and ethnically diverse , and the one not yet fully immersed in the housing and jobs market — is the generation that is likely to have the most profound impact on land use. Fifty-nine percent of Gen Y said they prefer diversity in housing choices; 62 percent prefer developments offering a mix of shopping, dining and office space; and 76 percent place high value on walkability in communities.”[ref]See Robert Krueger, “Where Americans Want To Live: New ULI Report, America In 2013, Explores Housing, Transportation, Community Preferences Survey Suggests Strong Demand for Compact Development” (Urban Land Institute Press Release, May 15, 2013).[/ref]

Urban studies analyst Richard Florida also notes that cultural opportunities and creative jobs are increasingly attractive to young adults, and these are more often found in close-in, walkable neighborhoods or suburbs.

Many young adults are locating in small towns that have walkable Main Streets and historic housing.

While it may seem that this change would put small towns, rural communities, and farther out suburbs at a disadvantage, this is not the case. As Leigh Gallagher notes her book, The End of the Suburbs,[ref]For more on The End of the Suburbs, see “Are We Headed For ‘The End Of The Suburbs’?” (on Here & Now; NPR & WBUR, Nov. 6, 2013)[/ref] many young adults are locating in small towns that have walkable Main Streets and historic housing.

New Urbanist development has been an effective way to retrofit older suburbs and create new developments in suburban areas that are attractive to young adults. Many young adults will move to suburban communities as they have children. Places that have quality schools as well as amenities like walkable neighborhoods, recreation, and open space will be very attractive to them.

Rural areas with quality schools and opportunities for parents to be involved will be especially attractive to some Millennials as they have children.

Rural areas may have fewer multimodal transportation options, but likely have historic commercial areas, good access to natural assets and recreation, and major advantages in the size of community. Many young parents would prefer to send their children to smaller schools where their children are less likely to fall through the cracks. Rural areas with quality schools and opportunities for parents to be involved will be especially attractive to some Millennials as they have children.[ref]See, e.g., “Making Rural Communities Desirable Places to Live” (Center for Rural Affairs; Lyons, Nebraska).[/ref]

What Can Planning Commissioners Do?

Planning commissions can create opportunities and environments that offer a high quality of life. Quality of life should, in fact, be at the core of what planning commissions consider during comprehensive planning efforts.

The following is a list of questions that planning commissions might want to consider when planning for quality of life and vibrant community life:

If unique assets (for example, outdoor recreation or historic sites) surround your community, there is a good chance that residents in your community use them. Indeed, they may be part of what has drawn new residents to the community.

What are the regional assets? -– Residents (including young adults) do not consider municipal and neighborhood boundaries in the same way that local government does. If unique assets (for example, outdoor recreation or historic sites) surround your community, there is a good chance that residents in your community use them. Indeed, they may be part of what has drawn new residents to the community. These are strong building blocks for local quality of life

What does it cost? -– This question relates to both what the amenities cost to build — always an important consideration for planning commissions and city councils! — and what it may cost to use the amenity. Oldenburg stresses that high quality third places are often free or inexpensive. While finding a proprietor of a fine restaurant is always a nice addition to the local shopping district be sure to consider who may be served and who may not be able to access a new amenity based on its cost of use. This may be especially important for young adults who are often dealing with tight budgets, paying off loans, and the costs of starting a family.

Are we covering the basics? — Research on amenity development that promotes economic growth suggests that sticking to basic building blocks of quality of life — recreation and the environment, transportation alternatives, and education — are the best levers to attract residents and jobs.[ref]See P.D. Gottlieb, “Amenities as an Economic Development Tool: Is There Enough Evidence?” (Economic Development Quarterly 8 (3),1994), pp. 270–285.[/ref]

Planning commission meetings and comprehensive planning efforts are good times to take stock of assets that may be tied together. For example, could school facilities be used for public recreation during the evenings and weekends? Sometimes different entities such as the school board or neighboring towns may be willing to share costs for quality of life facilities that can be expensive alone.

These basic amenities are important third places because they connect different types of residents from across neighborhoods. Schools matter to most residents and many share parks and recreation areas. These amenities can encourage community discourse.

Are assets connected? -– Planning commissions develop a vision of the community and plans for where housing, commercial, recreational, and other land uses will be developed. They also often have a significant say about public spaces and infrastructure, such as parks, trails, sidewalks, and the streetscape. These spaces and connections between home and work are a key part of what makes a community’s quality of life.

Planning commissions should also keep in mind the importance of a different type of connection. Small businesses and commercial districts often benefit from networks and coordination. Is there a chamber of commerce, retail association, or Main Street organization? If not, the commission may want to encourage and assist the business or retail community in starting one. If there is, involving a planning commissioner or two can help keep the commission aware of concerns and developments in the retail and business community.

Summing Up:

Young adults have turned towards walkable and vibrant communities and neighborhoods, often because of opportunities to live near third places. While many young adults have chosen urban areas for their early adulthood, suburban and rural areas have amenities that are also attractive. Young adults may move towards these communities as they move through life stages as well.

Often basic improvements in the streetscape and alternative transportation can act as a catalyst for new developments that improve shopping and dining options as well. These amenities are attractive for a resident’s quality of life, but may also improve the civic discourse in the community. Planning commissions can coordinate, plan, and create opportunities for improving amenities and a quality of life that is attractive to young adults and are open and accessible for the wider public as well.

Stuart Andreason is a doctoral candidate in the Department of City and Regional Planning at the University of Pennsylvania where he studies community and economic development. He previously researched civic innovation in community participation.

Prior to entering graduate school, Stuart worked as the Executive Director of a Main Street Organization, the Orange Downtown Alliance, in Orange, Virginia.

A Response from Jennifer Wallace-Brodeur:

Stuart has done a good job articulating quality of life issues and how they connect to young adult preferences when it comes to choosing a community in which to settle. Many of the strategies that will attract young adults also create an environment in which older adults can thrive. This is particularly true of the focus on walkability and the ability to connect to important community destinations.

AARP research on livable communities shows a correlation between community engagement and indicators of successful aging.

Community engagement and social connection are essential to health and well-being. The Blue Zones project,[ref]Blue Zones Project web site.[/ref] which came out of a study of societies with the greatest longevity in the word, identifies nine elements[ref]The nine elements identified in the Blue Zones Project are: 1. Move Naturally; 2. Purpose; 3. Down Shift; 4. 80% Rule; 5. Plant Slant; 6. Wine @ 5; 7. Belong; 8. Loved Ones First; and 9. Right Tribe. Go to the Blue Zones page for explanations of what some of these cryptic-sounding titles mean.[/ref] that contribute to a long life. Among them, three speak directly to human connection. The others relate to food, physical activity, and even enjoying a glass of wine every day.

AARP research on livable communities shows a correlation between community engagement and indicators of successful aging.[ref]Beyond 50.05 A Report to the Nation on Livable Communities: Creating Environments for Successful Aging (AARP, 2005) pp. 22-45.[/ref]

This is all to say that quality of life and the role of “third places” is not just about attracting young people, but it’s about the long term health of your community.

Stuart has identified good strategies to foster high quality of life. His discussion of the cost of amenities for patrons is particularly apt. In my neighborhood, the corner bagel café is the primary gathering spot for many older residents.

A recent controversy erupted in Queens, when the police were called in to disperse seniors who were spending long days socializing at the local McDonalds.[ref] Sarah Maslin Nir and Jiha Ham, “Fighting a McDonald’s in Queens for the Right to Sit. And Sit. And Sit” (The New York Times, Jan. 14, 2014).[/ref] It’s a good reminder that a table or bench and a cup of coffee are often all we need to create a good gathering place. When you look at creating these spaces, it’s also important to consider whether your current code allows for mixed-use development, particularly in traditionally residential areas.

It can’t be stressed enough how important it is to consider transportation and whether community amenities can be accessed by people who cannot drive.

It can’t be stressed enough how important it is to consider transportation and whether community amenities can be accessed by people who cannot drive. More than 50 percent of non-drivers over age 65 do not leave home most days, partly because of a lack of transportation options.[ref]See Linda Bailey, Aging Americans: Stranded Without Options (Surface Transportation Policy Project, 2004, Executive Summary; pdf).[/ref] As planning commissioners, you can bring the sometimes disconnected worlds of transportation and land use planning together for a holistic view of how to foster development of community amenities, as well as how people will access them. We will address transportation more extensively in an upcoming column.

One other issue is important to take note of: public safety. Crime can be the primary barrier to quality of life. It keeps people from walking, from accessing public parks, from interacting with neighbors, and can lead to the overall decline of the community.

Jane Jacobs coined the phrase “eyes on the street” and the idea that a vibrant community with engaged residents contributes to a safer neighborhood.

As planning commissioners, we can play an important role in creating safe environments, such as encouraging development that allows for active ground level space and buildings that orient to the street and sidewalk. Form-based codes, with their emphasis on how buildings look and fit in a neighborhood, are a tool that can help with this. Editor’s Note: we’ll be providing a primer on the use of form-based codes this spring.

Jennifer Wallace-Brodeur has been at AARP since 2005, serving as Associate State Director in the Vermont State Office until 2013, and then moving to the national office as Senior Advisor States. In Vermont, she led the Burlington Livable Community Project, which established a vision and action steps for Burlington to meet the needs of its aging population. This was one of AARP’s first local livable community projects. She also led AARP’s campaign to pass Complete Streets legislation in 2011, which earned her the Outstanding Service Award from the Vermont Planners Association.

Jennifer is active as a community volunteer, currently serving on the Burlington Planning Commission and previously as chair of the Burlington Electric Commission. In 2012, she was appointed to the Governor’s Commission on Successful Aging and served as chair of the livable communities subcommittee.