Street Width & Safety

The safety issue takes different paths to achieve that same objective, safer street for pedestrians. New urbanists focus on narrow streets as the most effective way to slow traffic, combining that with increased access points to a neighborhood, allowing for traffic to be more evenly distributed. Others advocate traffic calming devices, particularly as solutions in established neighborhoods with already built wide streets.

The safety issue takes different paths to achieve that same objective, safer street for pedestrians. New urbanists focus on narrow streets as the most effective way to slow traffic, combining that with increased access points to a neighborhood, allowing for traffic to be more evenly distributed. Others advocate traffic calming devices, particularly as solutions in established neighborhoods with already built wide streets.

New urbanists have been on the forefront of advocating narrower neighborhood streets that: (1) slow traffic to 10 and 15 miles per hour; (2) respect and protect the pedestrian; and (3) promote streets as neighborhood activity areas.

The move toward narrower streets, as proposed in most all new urbanist developments, has met with resistance, chiefly from fire and emergency safety officials in communities where established standards of wide streets have been in place for many years. Both sides — the fire / emergency safety establishment and the new urbanists upstarts — have armed themselves with empirical data proving they are right.

The move toward narrower streets, as proposed in most all new urbanist developments, has met with resistance, chiefly from fire and emergency safety officials in communities where established standards of wide streets have been in place for many years. Both sides — the fire / emergency safety establishment and the new urbanists upstarts — have armed themselves with empirical data proving they are right.

To assist you in deciding where you stand, let’s look at some of the data and issues in the debate to help you decide what is best for your neighborhoods and community.

Originally published in 1977, and updated in 2002 and 2006, Swift & Associates (Swift) – a Boulder, Colorado town planning, civil and traffic engineering firm – published a report –“Residential Street Typology and Injury Accident Frequency” — that examined data from 20,000 injury accidents in suburban Longmont, Colorado. The objective of the Longmont study was to create a method of empirically analyzing whether neighborhood street width affects injury accident frequency.

Within the study, Swift focused on a range of street and neighborhood characteristics. The characteristics included street curves, street widths, tree density, parking density, sight distance, and similar items. The resulting accident numbers were placed in a multiple regression analysis and compared.

The conclusions of the Swift study found substantial differences between injury accident frequency on narrow and wide streets. If we use Swift’s findings and compare them to the three different street widths we discussed yesterday, you get some striking results — an average of

- 0.07 accidents per mile per year (a/m/y) for the 29 foot wide street;

- 0.16 a/m/y for the 35 foot wide street; and

- 0.27 a/m/y for the 39 foot wide street.

The increase in accidents per mile per year between our three streets is quite substantial: 128% between the 29 and 35 foot wide; 68% between 35 and 39 foot wide; and a whopping 286% between 29 feet and 39 feet.

The Swift study demonstrates that a strong relationship exists between street width and an increase in the number of injury accidents. Narrow streets are safer than wide streets.

But one thing the Swift study did not look at was the relationship between street width and increased vehicle speed. In 1997, James Daisa and John Peers, both professional engineers, published a study titled “Narrow Residential Streets: Do They Really Slow Down Speeds?” based upon a study done in San Francisco. The conclusions of their study were that wider residential streets experience higher speeds, and that presence of on-street parking significantly affects vehicle speeds in residential neighborhoods. This is no surprise because we see the cause and effect of wider streets and speed every day.

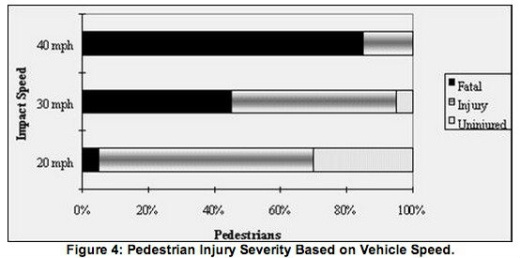

The final piece of the puzzle is the relative survivability of pedestrian / vehicle injury accidents and speed.

The final piece of the puzzle is the relative survivability of pedestrian / vehicle injury accidents and speed.

The FHWA notes 1 that a pedestrian has a:

— 95 percent chance of surviving being struck by a vehicle traveling 20 mph;

— 55 percent chance at 30 mph; and a

— 15 percent chance at 40 mph.

Combining the findings of the street width and the vehicle speed studies we can deduce that narrower streets reduce accidents and lessen severe injuries. Wider streets increase accidents and encourage drivers to speed resulting in more severe injury accidents.

The question remains regarding street width and adequate passage for fire emergency vehicles. 2 To determine the adequacy of emergency access, these items should be taken into consideration.

1. Is there sufficient street width to provide an average passage width of 20 feet even when parking is permitted on both sides of the street? (An average passage width is where 20 feet is available for more than half of a street’s length).

2. Is there enough connectivity in the neighborhood where responders have multiple choices of access to an emergency? Many suburban neighborhoods have long stretches of streets with minimal connectivity. In contrast, new urbanist developments stress multiple points of connectivity to disperse average daily trips.

Summing Up:

There’s more to our neighborhood streets than just providing the fastest access possible for residents. It’s more important for us to be aware of empirical data on the relationship between street width, vehicle speed, and safety. At the same time, we need to balance legitimate concerns by fire departments against the fact that wider streets have been shown to result in significantly higher injury accident rates.

Steve McCutchan works as a land planning and urban design consultant for Blu Line Designs, a Salt Lake City, Utah land planning, urban design, and landscape architecture firm and specializes in preparing master planned communities, planned developments, site plans, and subdivisions for the Mountain West’s land development and home building industries.

In addition to his more than 37 years of professional experience, Steve has worked to broaden his career by lecturing, teaching and writing on land planning, urban design and land development. He has lectured and taught at universities in California and Utah and contributed to professional journals throughout the United States. Steve is the recipient of an American Planning Association’s National Award for Outstanding Planning for comprehensive planning and several chapter awards for urban design.

In upcoming columns, Steve will be taking a closer look at a range of land use and development issues, such as creating sustainable neighborhoods centered around schools; the future of suburban shopping malls; and the extent to which residential development pays for itself.

Notes:

- Pedestrian Facilities User Guide – Providing Safety & Mobility (FHWA, 2002), Pedestrian Crash Factors, p. 13. See also Impact Speed and a Pedestrian’s Risk of Severe Injury or Death (AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety, 2011); the AAA study also compares risk of injury or death by age group). ↩

- Editor’s Note: for some good observations on street width and fire equipment access, see Dan Burden, “Street Design Guidelines for Healthy Neighborhoods” (from TRB Circular E-C019: Urban Street Symposium; 1999). Burden notes that after a team of engineers, planners, architects, and others measured and analyzed residential streets in a number of communities: “although we found that 26-foot-wide roadways are most desirable, we measured numerous 24-foot and even 22-foot wide roadways, which had parking on both sides of the street and allowed delivery, sanitation and fire trucks to pass through unobstructed.” ↩