Read the start of this article below; to view full article you need to be a PlannersWeb member. Already a member? — be sure you’re logged-in. Not a member? Consider joining the PlannersWeb.

In responses to a questionnaire we sent out last Spring, “Low Impact Development” (also often referred to as low impact design) was at the top of the list of subjects that readers want to know more about. In this series, Lisa and Jim will explain the basics of LID, how it works, why your community may need it, how LID costs compare to conventional stormwater management, and the type of ordinances that have worked to implement LID in communities around the country.

Part 1: What is LID?

Low Impact Design is the terminology used in the United States primarily to designate a land planning and engineering design approach to stormwater management which emphasizes conservation and the use of on-site natural features to protect water quality. (Later in this series, we’ll make the case for a broader definition of LID.) This definition is important because conventional development treats stormwater as a waste product that is conveyed offsite and disposed of. Let’s look at the definition of stormwater and at our history of stormwater management to help establish the context for LID.

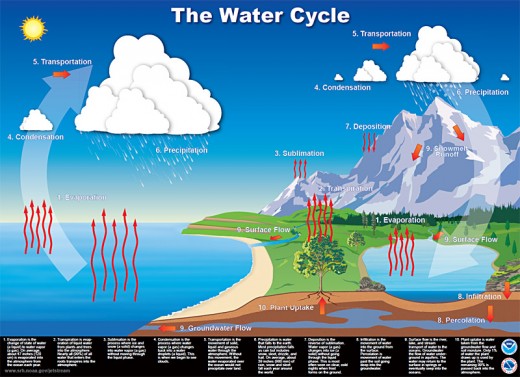

Stormwater: a term used to identify water that originates during precipitation events. Simply put, it is rainfall that contacts the earth’s surface. Stormwater is a natural part of the hydrologic cycle, which you may recall from your middle school earth science class. Water vapor collects in the atmosphere, which becomes clouds, which becomes rain, which recharges groundwater and surface water, which evaporates to become water vapor … and this is a continuous dynamic cycle.

This simplistic explanation leaves out the details of how rainfall recharges both groundwater and surface water, a dynamic balance that depends on many variables at a given location, including the characteristics of the natural and built environments in the watershed.

Generally speaking, in an undeveloped watershed, about half of the rainwater infiltrates the land and becomes groundwater, while the other half travels via overland flow to join streams and rivers. However, the exact ratio of surface and groundwater recharge by rainfall varies according to climate, soils, slope, ground cover, and other specific conditions in the watershed.

When human settlements began significantly altering land cover patterns, the behavior of rainfall on the land surface was changed. As the built environment increasingly favored impermeable surfaces (rooftops, paved roads, and other urban “hardscapes”), the disposition of rainfall changed, causing more of the rain that fell to run off the land and less to infiltrate to recharge groundwater.

As we continued to develop the land surface, we caused greater volumes of rainfall to run off at the expense of groundwater infiltration. Over time, rainfall runoff volumes in urban areas became so significant that we began treating it like a waste product to be conveyed away from developed areas as quickly as possible.

Open concrete channels are a common part of our stormwater infrastructure. They move water efficiently away from urbanized areas, but prevent the normal interaction of rainfall and land.

Our continued pattern of urbanization has resulted in multiple problems:

Our continued pattern of urbanization has resulted in multiple problems:

End of excerpt

You must be logged in or a PlannersWeb member to read the rest of the article.