by PCJ Editor Wayne Senville, reporting from Scranton, Pennsylvania

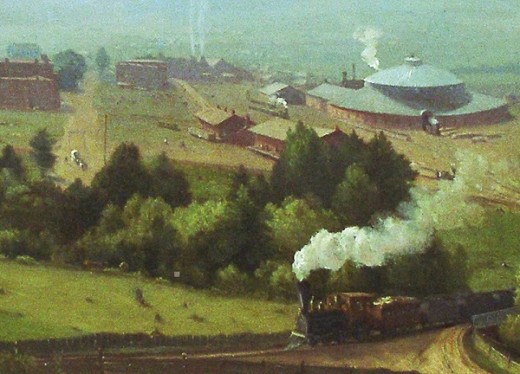

What, you’ve never heard of “Steamtown”? As you can see from the photo, it’s not about steam coming up out of the ground; it’s about steam bellowing from locomotive engines.

Steamtown is a National Park site located in downtown Scranton, Pennsylvania. In part, it was the “gift” of powerful Congressman Joe McDade to his district back in 1986, despite vociferous criticism within the “railroading community,” which for many years had been advocating a national park devoted to railroading — but not in Scranton.

I should know, because I was part of the National Park Service team that worked on the initial development plan for Steamtown in 1986 and 1987. At the time, Steamtown represented a diverse (and some would say disheveled and poorly maintained) collection of railroad equipment that had been salvaged by the City of Scranton from a non-profit that had operated Steamtown in Bellows Falls, Vermont.

The site of the park was to be on the downtown rail yard, formerly owned by Delaware, Lackawanna & Western. It was far from the grandest in the country. The rail yard’s original roundhouse, where engines were stored and turned, appear in a famous 1855 painting, The Lackawanna Valley, by American artist George Inness (see a portion of that painting below).

It would be the key feature of the park. Yet only a remnant of the original was still in existence when our Park Service team arrived in Scranton to begin preliminary planning studies.

Moreover, we soon learned that the rail yard was about to be sliced up, with about a third of it being promised for a new downtown shopping mall.

Any guesses how Scranton got the federal funds needed to build the mall? Think politics, again.

So it was with that luggage that Steamtown became a unit of the National Park System. But I can tell you from my own experience, that the Park Service has some very talented people, and with the initial infusion of some $60 million Steamtown was up and rolling. Take a look at a portion of the rebuilt roundhouse below (and for steam purists, yes Steamtown does own & operate one diesel).

I visited Steamtown on Friday to see how it was faring, and learn what sort of difference it was making to Scranton. I had hoped to get some hard numbers, in terms of where visitors to Steamtown were coming from, how long they were staying in the Scranton area, and how much they were spending. Unfortunately, Park Service Superintendent “Kip” Hagen (interestingly enough, a native of Scranton) didn’t have that information. Park Service regulations, he noted, bar collecting this kind of personal visitor information.

Earlier in the day, Austin Burke, President of the Greater Scranton Chamber of Commerce, had told me that up until 2000 the Chamber had prepared reports for the Park Service on Steamtown visitor trends and expenditures. Burke pulled out a copy of the last report and handed it to me. In the year 2000, Steamtown had 160,421 visitors, 61,120 of whom stayed overnight in the area. Total visitor expenditures came to $8.3 million dollars, or about $52 per capita.

Earlier in the day, Austin Burke, President of the Greater Scranton Chamber of Commerce, had told me that up until 2000 the Chamber had prepared reports for the Park Service on Steamtown visitor trends and expenditures. Burke pulled out a copy of the last report and handed it to me. In the year 2000, Steamtown had 160,421 visitors, 61,120 of whom stayed overnight in the area. Total visitor expenditures came to $8.3 million dollars, or about $52 per capita.

Burke also expressed frustration with the lack of commercial opportunities provided by Steamtown. For example, a local bank can’t sponsor an excursion train (note: one of the features of Steamtown is that the Park Service runs 34 “main line” excursion trips beyond Scranton, and many daily train trips within the vicinity of the Park). Again, as Park Superintendent Hagen told me, his hands are tied as federal regulations prohibit this. View a short video clip I took of one of the Steamtown trains heading through Scranton.

But let’s put aside economics and consider other impacts Steamtown has had on the community.

But let’s put aside economics and consider other impacts Steamtown has had on the community.

Superintendent Hagen and Chief of Interpretation Mark Brennan described a hugely successful volunteer program, drawing on Scranton residents, as well as some from further afield. Many are rail fans. But as Brennan noted, “they learn to separate the rail fan world from the real world of railroading” that Steamtown’s operations involve.

Some aim for that ultimate goal: becoming a Steamtown engineer. This past year, Brennan told me, there are 70 volunteers in “rail operations” and 16 in “visitor services.”

Volunteers range in age from 16 to 85, and include teachers, carpenters, two priests, an oncologist, salesmen, and some folks who work within the railroad industry (including an Amtrak engineer).

It’s a tough process to secure work as a rail operations volunteer at Steamtown. Training must comply with Federal Railway Administration rules, and includes 40 hours of classroom training and considerably more in the field. Volunteers are closely supervised, and it can take five or more years to get from “trainman” (the initial volunteer assignment) to engineer. Yet most volunteers stick with it. In 2006 Superintendent Hagen received special recognition from Take Pride in America for the Steamtown volunteers program.

Why is there such keen interest and commitment among volunteers? Brennan told me it almost always amounts to a love for steam — for the power, the intensity, the sounds, of steam-powered railroading. [see the following two short video clips; in the first one I get “steamed” while taking the video]

One other example of using volunteers: under the supervision of a National Park Service historian, over the past two years some 60 Scranton area high schoolers have been helping Steamtown, while earning community service credits.

They’ve done this by entering personnel records and business documents from the old Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad (DL&W) into the Park’s database. In the process, Brennan told me, “many have become fascinated by what they’ve found out about their own community.” It’s not just idle work. The aim is to have a database where visitors to Steamtown can look up relatives or other people they know who might once have worked for the DL&W.

They’ve done this by entering personnel records and business documents from the old Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad (DL&W) into the Park’s database. In the process, Brennan told me, “many have become fascinated by what they’ve found out about their own community.” It’s not just idle work. The aim is to have a database where visitors to Steamtown can look up relatives or other people they know who might once have worked for the DL&W.

Steamtown is far from your usual Park Service operation. It’s surely the only National Park with a staff of six professional mechanics needed to maintain railroad engines, coaches, and assorted other equipment. In addition to running a small rail operation, there’s an excellent museum and exhibits on the site.

Given tight federal budgets, Steamtown has had to operate quite frugally after its initial cash infusion in the late 1980s when the park started up (and it wasn’t cheap to reconstruct the roundhouse, the central element of Steamtown). But, as Hagen pointed out, the volunteers provide a critical “free” resource. He’s calculated that volunteers last year put in some 15,000 hours of work. This is the equivalent to about 9 full-time employees — which adds up to a substantial monetary value.

But it’s all attributable to a love for steam.