Read an excerpt from this article below. You can download the full article by using the link at the end of the excerpt.

Since planners were among the earliest adopters of GIS, there is no shortage of interesting applications to showcase. However, since I have a limited amount of space, I thought I’d share with you three useful (and, I hope, interesting) GIS applications.

1. GIS and Build-Out Analysis

A build-out analysis can be a highly useful exercise for a town that would like to monitor development policies (zoning) and their impact on community infrastructure, aesthetics, and economy. Typical build-out analyses help communities deal with questions such as:

- How much land can be developed under existing land use regulations, and where will this growth take place?

- What is the number of residential lots available to be developed, and what will the town’s population be at full build-out?

- Do the densities of development called for in the town plan seem appropriate to their location, existing infrastructure, and aesthetics?

- Are there areas of the town zoned for development that the community may want to consider keeping undeveloped?

Pine Plains, New York (population 2,569 as of the 2000 Census) with the help of a consultant (Community Planning & Environmental Associates) used a GIS based approach to conduct a build-out analysis for the town that included a proposed Hamlet District.

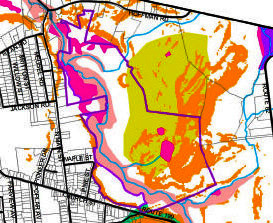

The process began by taking the parcel map and dividing it into the proposed Hamlet District and all areas outside the Hamlet District.

The second step was to use the GIS to identify all parcels that would not allow additional development (road, utility, and right of way corridors; fully built parcels; and parcels with conservation easements).

The third step was to identify environmentally constrained areas as recommended by the town plan (but not yet adopted in the town’s development regulations). These areas included 20 foot buffers of streams; wetlands; slopes greater than 15 percent; shallow soils; and the 100 year flood hazard zone.

The final step was to calculate potential new residential units for each parcel using a variety of scenarios that manipulated minimum lot size or environmental control weighting.

End of excerpt