America is a relatively young civilization, measuring its history in hundreds, rather than thousands, of years. With a seemingly inexhaustible supply of new and largely undeveloped land to the west (excluding from consideration, as unfortunately most did, the preexisting Native population) many Americans were uncommitted to long-term occupation of a particular place. Neighborhoods, communities, and even entire regions were used for their immediate benefits and then permitted to deteriorate in the name of “progress.”

America is a relatively young civilization, measuring its history in hundreds, rather than thousands, of years. With a seemingly inexhaustible supply of new and largely undeveloped land to the west (excluding from consideration, as unfortunately most did, the preexisting Native population) many Americans were uncommitted to long-term occupation of a particular place. Neighborhoods, communities, and even entire regions were used for their immediate benefits and then permitted to deteriorate in the name of “progress.”

Until the late 1920s, little was done to protect the urban artifacts of the nation’s cultural history -– other than the preservation and restoration of isolated structures associated with historic personages, such as George Washington’s Mount Vernon residence. But in 1929 this began to change with John D. Rockefeller, Jr.’s decision to restore the city of Williamsburg, Virginia, to its colonial-era glory.

In short order, other cities embarked on major historic preservation programs. In 1931, Charleston, South Carolina, placed its eighty-acre Battery District in a specially zoned historic preservation district.

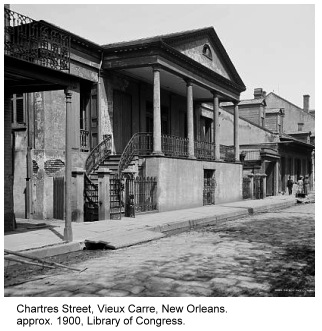

The following year New Orleans’ Vieux Carré became the first urban district in America to receive local landmark preservation status. These actions expanded historic preservation beyond individual structures to the preservation of entire urban districts of distinctive character.

The following year New Orleans’ Vieux Carré became the first urban district in America to receive local landmark preservation status. These actions expanded historic preservation beyond individual structures to the preservation of entire urban districts of distinctive character.

Urban Renewal, founded in the U.S. Housing Act of 1954, is most commonly remembered for large-scale central city demolitions (see J is for Justice). But among the distinguishing features of the Act was its emphasis on the rehabilitation of older central city homes. Section 701 of the Act made federal funds available to local governments for the preparation of historic district legislation and the development of historic preservation programs.

The most influential effort in historic preservation initiated with the support of Urban Renewal was the 1956 College Hill Study undertaken by the Providence (Rhode Island) City Planning Commission and the Providence Preservation Society. Beginning with an extensive inventory of the 380-acre “College Hill” district, the project resulted in a historic area zoning ordinance; a system for rating historic architecture; and a technique for integrating historic architecture into a proposed central area redevelopment plan. Providence’s work served as a model for other communities to follow.

The demolition of New York City’s Pennsylvania Station in 1965, one of the nation’s most magnificent railroad stations, shocked many New Yorkers, as well as citizens across the country.

Outraged by the fact that there was no legal recourse to stop the demolition (the building was privately owned by the nearly bankrupt Pennsylvania Railroad), New Yorkers responded by enacting later that year a comprehensive landmarks preservation law. New York City now boasts the largest collection of designated landmarks of any municipality: nearly 1,000 individual landmark buildings, more than 100 interior spaces, and 70 historic districts comprising more than 20,000 buildings.

Outraged by the fact that there was no legal recourse to stop the demolition (the building was privately owned by the nearly bankrupt Pennsylvania Railroad), New Yorkers responded by enacting later that year a comprehensive landmarks preservation law. New York City now boasts the largest collection of designated landmarks of any municipality: nearly 1,000 individual landmark buildings, more than 100 interior spaces, and 70 historic districts comprising more than 20,000 buildings.

At the federal level, Congress enacted the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 which created the National Register of Historic Places; provided funding for the National Trust for Historic Preservation; and offered tax credits for housing rehabilitation in National Register Districts. Within twenty-five years of its passage there were over 8,000 historic districts listed in the National Register.

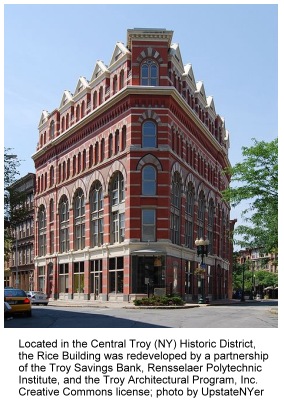

The scope of historic preservation broadened in the 1980s to include a focus on the link between economic development and historic preservation. The National Trust for Historic Preservation established a “National Main Street Center” to support local efforts to rehabilitate older commercial areas. In the last two decades of the twentieth century, Main Street programs generated more than $8 billion in physical reinvestment in the historic downtowns of over 1,300 communities.

The scope of historic preservation broadened in the 1980s to include a focus on the link between economic development and historic preservation. The National Trust for Historic Preservation established a “National Main Street Center” to support local efforts to rehabilitate older commercial areas. In the last two decades of the twentieth century, Main Street programs generated more than $8 billion in physical reinvestment in the historic downtowns of over 1,300 communities.

Editor’s Note: for a good primer, see our grouping of articles, “Planning for Historic Preservation.”