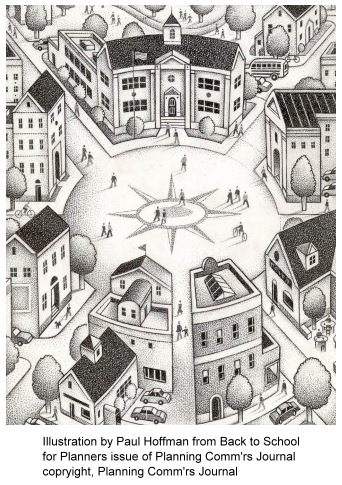

Concerns for the health and safety of children were central components of ideal urban structure theories of the early twentieth century. Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City, promoted in his book To morrow, a Peaceful Path to Real Reform (1898), consisted of six “neighborhood units” bounded by through-traffic streets, each with a central elementary school located just a few blocks from the furthest residence. Forest Hills Gardens, Long Island, New York (1910+), was the first American test of this schoolchild-focused neighborhood idea. See N is for Neighborhood.

Concerns for the health and safety of children were central components of ideal urban structure theories of the early twentieth century. Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City, promoted in his book To morrow, a Peaceful Path to Real Reform (1898), consisted of six “neighborhood units” bounded by through-traffic streets, each with a central elementary school located just a few blocks from the furthest residence. Forest Hills Gardens, Long Island, New York (1910+), was the first American test of this schoolchild-focused neighborhood idea. See N is for Neighborhood.

The culture shock of World War I brought on not only the wild excesses of the Jazz Age of the 1920s, but also a heightened perception of youth as the promise and salvation of the future. In the planned neighborhood developments of the 1920s, elementary schools were centrally located within easy walking distance of their student population.

The 1920s was also the first decade to feel the severe negative impact of the automobile, with thousands of school-age children being killed by motorists. In response, there was a movement to reduce or eliminate all through-traffic in new suburban developments. At Radburn (Fair Lawn, New Jersey) this emphasis on child safety resulted in the total separation of vehicular and pedestrian pathways. Here elementary-school-age children could walk from home to school through center-block parks without walking along or across a street.

The educational and recreational needs of older children were provided for in the 1920s in the siting of large, architecturally impressive, central high schools and their organized sports fields. These schools became integral components of town and city centers. High-school-age children thus had after-school access (either by foot or by electric trolley car or rubber-tired bus systems) to downtown or “Main Street,” where the retail shops, theaters, and other places of amusement were located.

With the explosive unplanned suburban sprawl of the 1950s and the decades that followed, concern for the life patterns of elementary-school and high-school age children became less evident. Safe local walk-in elementary schools, no longer viable with the lower densities resulting from the advent of large-lot residential zoning (as well as reduced family size), were abandoned in favor of more far-flung locations. New high-school facilities were often located on large tracts of open space at the perimeter of the community, often accessible only by school bus or automobile. Editor’s note: see Edward McMahon’s “School Sprawl” (PCJ, Summer 2000) and Tim Torma’s “Back to School for Planners” (PCJ, Fall 2004).

There are signs of a reversal in this decades long trend, as proponents of “New Urbanism” and “Smart Growth” advocate for higher density residential areas, permitting reclamation of the walk-in local elementary school, and increased provision of transit service, enabling older students to access central areas of the community without need for their own car.

There are signs of a reversal in this decades long trend, as proponents of “New Urbanism” and “Smart Growth” advocate for higher density residential areas, permitting reclamation of the walk-in local elementary school, and increased provision of transit service, enabling older students to access central areas of the community without need for their own car.

The growing number of “safe routes to school” programs also highlight a renewed interest in enabling young people to walk or bike to school. These programs are not only designed to provide health and safety benefits, but to better connect children with their communities and with the natural environment. Editor’s note: see Hannah Twaddell’s “Safe Routes to School” (PCJ, Fall 2004).