Read an excerpt from this article below. You can download the full article by using the link at the end of the excerpt.

Something is absent from many American suburbs.

Not schools; those are mandatory. Not housing; there’s plenty of that. Not gas stations, restaurants, and strip shopping; those abound, especially in suburbs that grew up after the Second World War.

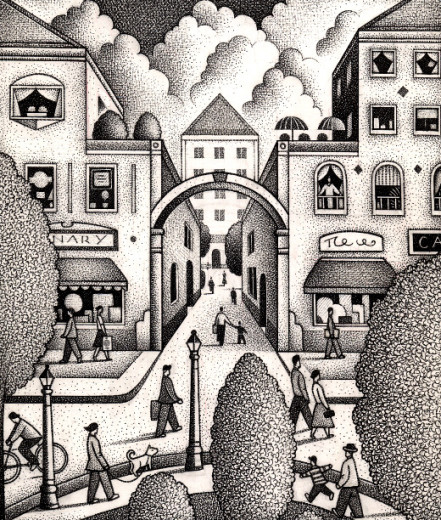

No, the ingredient missing from many suburbs is a “town center,” a place people head to for many different purposes — to shop, dine, visit a library, deliver a package to the post office, take in a movie or a concert, or just to enjoy being in an animated public place. Until the 1940s, nearly every sizable community had a center where people could conduct their everyday activities while feeling a buzz of sociability. The development of pedestrian-scale community hubs, however, ground to a halt as cities and suburbs became increasingly oriented to a sprawling, automobile-dominated land use pattern.

Now that’s changing. Since the beginning of Mashpee Commons on Cape Cod in the mid-1980s and the construction of Mizner Park in Boca Raton, Florida, in 1990, mixed-use town centers have become an ever more common type of development. Sidebar, Mizner Park. They are cropping up in all sorts of localities — from postwar bedroom communities, to new suburban areas, to old towns whose industries have collapsed, leaving “brownfield” sites that need new uses.

Defining a Vision

Town centers vary greatly in size, character, and purpose. To get a center that fits local desires, “the municipality must define its goals,” says Macon Toledano, vice president of Warwick, New York-based Leyland Alliance, which is developing a mixed-use center in the Town of Mansfield, Connecticut, near the University of Connecticut’s main campus.

Town centers vary greatly in size, character, and purpose. To get a center that fits local desires, “the municipality must define its goals,” says Macon Toledano, vice president of Warwick, New York-based Leyland Alliance, which is developing a mixed-use center in the Town of Mansfield, Connecticut, near the University of Connecticut’s main campus.

“The work of the municipality,” he says, “is in educating themselves as to the differences and defining their choices in advance” before seeking a developer.

A suburb that’s happy with postwar patterns of development may opt for what the real estate industry calls a “lifestyle center.” Lifestyle centers tend to arrange their stores and restaurants so that their doors and windows face onto sidewalks and a privately operated Main Street, as at “The Avenue at White Marsh,” a lifestyle center off Interstate 95 east of Baltimore. The centers’ large parking lots are usually situated on the perimeter, not visible from the main street. Only a small percentage of lifestyle centers have housing or office space. Despite their current popularity, some planners and retail experts worry that lifestyle centers, essentially open-air malls, won’t fare well in the long run but will lose appeal, as has already happened with many middling-quality enclosed malls.

If the goals of the municipality are those of new urbanism, smart growth, or sustainability, the community will tend to favor “concentrated, pedestrian-oriented, mixed-use environments with a focus on the public realm,” Toledano says. …

End of excerpt

You must be logged in or a PlannersWeb member to download this PDF.